The 1964 Asahi Pentax Spotmatic SP was the first commercially-available M42 SLR that combined auto-diaphragm lens operation with TTL light metering, but in a rather cumbersome two-step process. This third generation M42 technology would be employed by countless models by numerous manufacturers from the mid 1960s through the late 1980s. Like the Nikon F before it, the SP has generated quite a lore around itself where many folks believe it was the “best” or one of the best M42 bodies ever made. Given the wide range of later and better M42 camera body alternatives, is there an objective case for the SP? Let’s find out.

The M42 lens mount standard was developed before WW2 but did not come into general commercial use until the late 1940s. In 1949, East Germany’s Contax introduced the first of its “S” line of M42 SLR cameras. Other East German products such as the “Praktica” and “Praktina” line also appeared during the late 1940s and early 1950s. For its part, Pentax also entered the race, claiming that its 1952 Asahiflex I was the first Japanese-built M42 SLR to reach market.

Throughout the 1950s, M42 camera technology rapidly developed with the East German and Pentax models being competitive with each other. During 1956, Contax announced its “F” camera that introduced “auto-diaphragm” operation with M42 lenses that contained an extra “stop down” pin that permitted the camera body to hold the lens’ aperture wide open for focusing while automatically stopping down to the selected aperture upon taking the shot. Pentax’s ultimate response was the 1958 Pentax K, an auto-diaphragm-capable camera with an integrated pentaprism and a lever film advance. In 1961, Pentax introduced the S3, which could use an optional detachable coupled light meter.

When introduced in 1964, the SP’s primary innovation was a built-in TTL light meter with a match-needle exposure system. From the outset, the Spotmatic system had broad range of professionally-oriented accessories as well as a full-range of lenses from 17mm to 1000mm. Although the SP came standard with either a 50mm f/1.4 or a 55mm f/1.8, it could function equally well with any auto-diaphragm M42 lens. Pentax continued producing the Spotmatic series in various forms until about 1975.

In 1971, Pentax introduced the first of the fifth generation” of M42 SLRs with its “ES.” The ES was the first electronic-shutter, aperture-priority autoexposure M42 camera. For the system to function properly, however, Pentax required the use of proprietary lenses that contained the necessary linkages to communicate the lens aperture to the camera.

Specifications

| Year Introduced | 1964 |

| Lens Mount | M42 |

| Shutter | Metal Focal Plane |

| Shutter Speeds | B, 1 sec. – 1/1000 |

| Viewfinder Magnification | 0.88x (50mm); 1.00x (55mm) |

| Focusing Screen | Fresnel / Microprism |

| ASA Range | 20-1600 |

| Weight | 621g |

| Flash X-Sync Speed | 1/60 |

| Battery | PX400; 387S (Modern Replacement) |

Operation

Like many marquee 35mm camera bodies of the 1960s, there is little question that the SP exhibits exceptional build quality and attention to detail. There is a strong case that the SP is among the best of the third generation of M42 cameras.

Operation: In 1964, the primary draw of the SP would have been its ability to use any auto-diaphragm M42 lens with true built-in TTL light metering. Remember that even the Nikon F and F2 require the use of an optional external prism for TTL metering. The SP employed a two-step procedure for it to work. Essentially, when an auto-diaphragm M42 lens is mounted, the camera body holds the aperture wide open for the purposes of easy focusing. To meter at a selected aperture, you press the switch at the side of the lens mount to turn on the meter and to stop down the lens to the taking aperture. A needle will then begin moving in the viewfinder, and you would change the aperture and shutter speed combination until the needle falls between the + and – signs. You then switch off the meter, which returns the lens to wide-open aperture. When triggering the shutter, the body automatically stops down the lens to the selected aperture. The shutter noise is not particularly quiet.

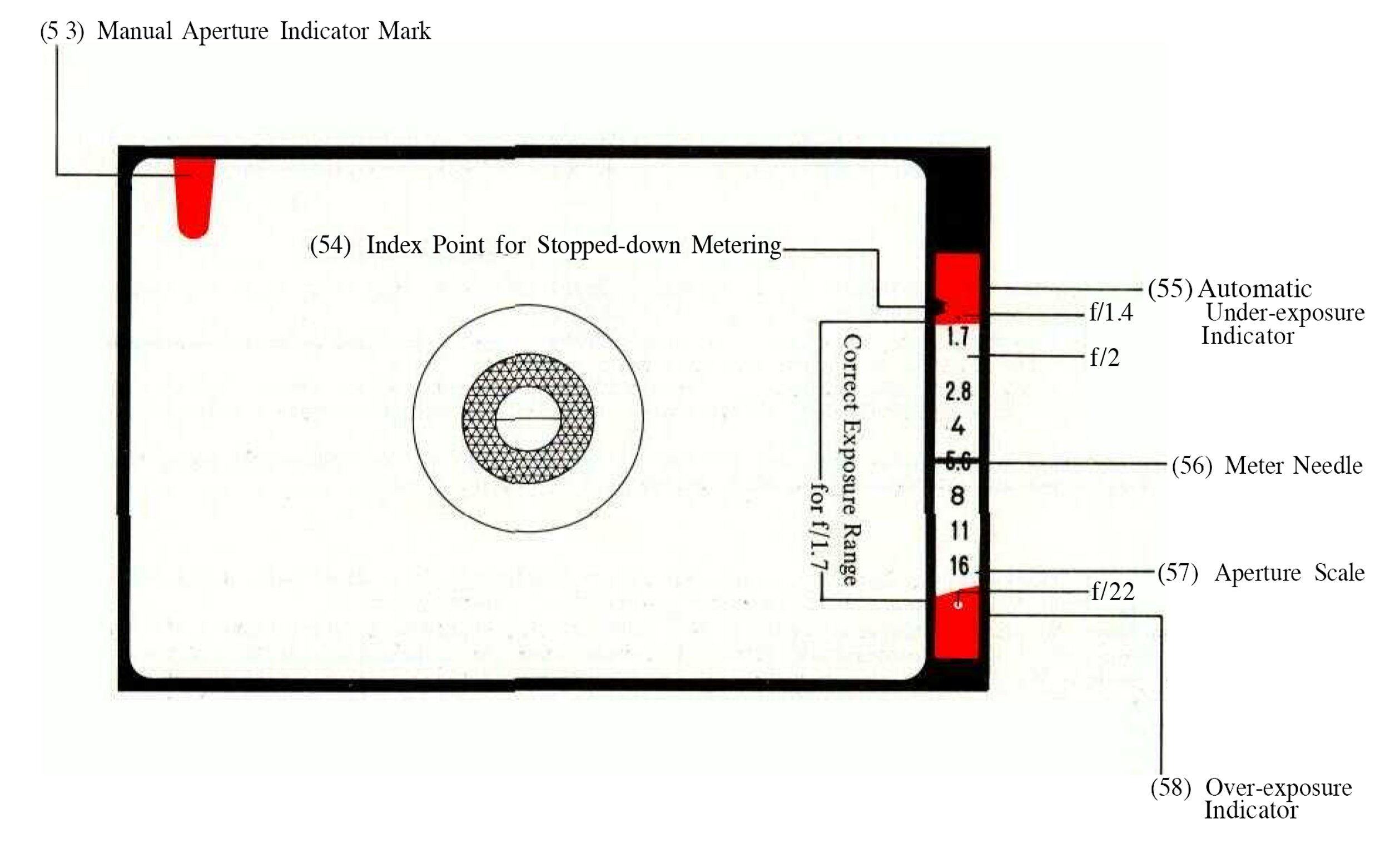

Viewfinder: The only information displayed in the viewfinder is the match-needle information on the right side of the screen. The fixed, non-interchangeable focusing screen is a fresnel / matte microprism type with a .88x magnification with the 50mm lens and 1.00x magnification with the 55mm lens. The focusing screen is not exceptionally bright, even with a f/1.8 lens, and is mostly par for the course for a 1960s camera of this type.

Lack of Flash Shoe: The SP did not come standard with either an integrated cold or hot shoe for a flash. A cold shoe adapter that fit over the camera’s viewfinder was an optional accessory. The SP has two flash sync sockets on the front of the camera for “X” and “FP.”

No Motor Drive Capability: The original SP does not have the appropriate linkages for the Pentax’s later motor drive. However, Pentax later produced in 1967 a variation of the SP called the “Spotmatic Motor Drive.” With a bottom-mounted unit, the camera could achieve 2-3 frames per second at 1/1000. Read all about this motor drive and the optional 250 frame back here.

Batteries: The SP used a single V400PX 1.35 mercury battery to power the meter. The most common alternative today would be a zinc air MRB400 1.35V battery. Many SP users claim that, unlike other 1960s cameras, the 1.55V of modern alkaline batteries will not throw off the camera’s meter. The closest alkaline equivalent that works appears to be a 387S, which is just a 394 battery with a rubber ring.

Shutter Speed / ISO Range: Typical for the era, the SP had shutters speeds of “B” and 1 second to 1/1000. No SLR camera of the 1960s, save for 1960 Konica F, the 1960 Canonflex R2000, and the 1964 Leicaflex, offered a faster shutter speed than 1/1000. ISO range is 20 to 1600.

Self-Timer: The SP has the standard mechanical front self-timer.

Exposure Lock: The SP has no external exposure lock and no manual exposure compensation.

Conclusions

In my opinion, the SP suffers a bit from “conventional wisdom” syndrome. While no doubt a quality-made and innovative SLR from an age where manufacturers placed more of a priority on aesthetics and durability, the SP has been completely eclipsed by several subsequent generations of M42 cameras. The main drawbacks for me are the cumbersome metering process and the relatively dark viewfinder with any lens slower than f/1.8, with the obscure battery thing being a secondary concern. This may be heresy to some, but if looking for a native film platform for M42 lenses, there are plenty of better options.