Sometimes you do not choose a camera, a camera chooses you. This is certainly the case with my father’s well-worn and still-functional Nikon N2020 (or F-501 outside of North America). The N2020 is a pretty well-made and capable body, hobbled by a relatively dark viewfinder and a slow, loud autofocus system that does not function well in low-light conditions.

By the early 1980s, the race to develop a viable autofocus SLR was on. While Pentax technically produced the “first” example, the 1981 ME F, it was slow, clumsy, and could only use a single dedicated 35-70 lens. The following year, both Canon (AL-1) and Yashica (FX-A) introduced bodies with “focus assist,” a manual focus system where the camera’s sensors could indicate to the user when the subject in the crosshairs was in focus. In 1983, Nikon introduced its own clumsy F3AF with could autofocus only a proprietary 80mm and 200mm lens. In 1985, Minolta beat everyone to the punch with the Maxxum 7000, the first modern and functional autofocus camera sporting a top mounted LCD screen for exposure feedback. Nikon would not produce with a camera with both autofocus and an top-mounted LCD info screen until the 1988 N8008 (F-801).

During 1985, Nikon introduced the N2000 (F-301). A complete break from the prior FG series, the N2000 represented a series of firsts: (1) a body made of polycarbonate; (2) an integrated motor drive with auto film loading and advance (but no rewind); and (3) the capability to read DX-coded film cassettes. The N2000 had far more electronic functionality than any Nikon body before it, even the fabled F3 and FA. Although the FA was the first Nikon body with a “program” mode, the N2000 had two program modes (high and normal) as well as retaining an aperture priority and a manual mode.

In 1986, Nikon introduced the N2020 (F-501), essentially an N2000 with autofocus. The N2020 had the additional feature of a “dual program mode,” which switched to “program high” for lenses 135mm and longer and regular “program” mode for lenses shorter than that. The N2020 could also take three different focusing screens not available on the N2000. By the time the N2020 was discontinued in 1989, Nikon’s flagship F4 had appeared and autofocus modules were already in the next generation. For future cameras, Nikon did not retain any aspects of the N2000/N2020 design.

The N2020 is certainly an interesting interregnum camera. While it was a great leap forward from Nikon’s late 1970s and early 1980s FG/FE/EM series, it also came before the 1990s mass-plastification of consumer SLRs. While an interesting piece of Nikon history, I am not so sure if it is a good choice for a daily shooter today.

Specifications

| Lens Mount | Nikon F |

| Shutter | Electronic Vertical Metal |

| Full Lens Compatibility | Ai, Ai-S, AF & AF-D |

| Focus Modes | AF, Focus Assist & Manual |

| Exposure Modes | Aperture, Program & Manual |

| Shutter Speeds | B, 1 sec – 1/2000 |

| ASA Range | 12-3200 (Non-DX); 25-5000 (DX) |

| Motor Drive | Load & Advance; Up to 2.5 FPS |

| Flash Sync | 1/125 |

| Batteries | 4 x AAA (MB-4); 4 x AA (MB-3) |

| Weight | 604g |

Operation

Lens Compatibility: While Nikon retained its “F Mount” up until its newest Z mirrorless cameras, the N2020 cannot use with full functionality the entire range. The N2020 can utilize Ai, Ai-S, Series E, AF, and AF-D lenses. After that, things get a little dicey. Screw-drive G lenses will autofocus but will only work in program mode. Modern AF-S lenses will kind of work: they will not autofocus, but in program mode only, they will meter, focus assist, and take a shot. With screw-drive G lenses or AF-S lenses, the N2020 will not be able to tell you what the shutter speed or aperture are. AF-P lenses will not work at all.

Viewfinder: The N2020 has a decent, uncluttered, and not especially bright viewfinder that displays LEDs for the shutter speed along the right side and the focusing indicators at the bottom. The camera came native with a “Type B” focusing screen but can be replaced with proprietary “Type J” (matte / fresnel with a centered microprism) or “Type E” (grid). The different screens will not affect the autofocusing and are only aids for specific uses.

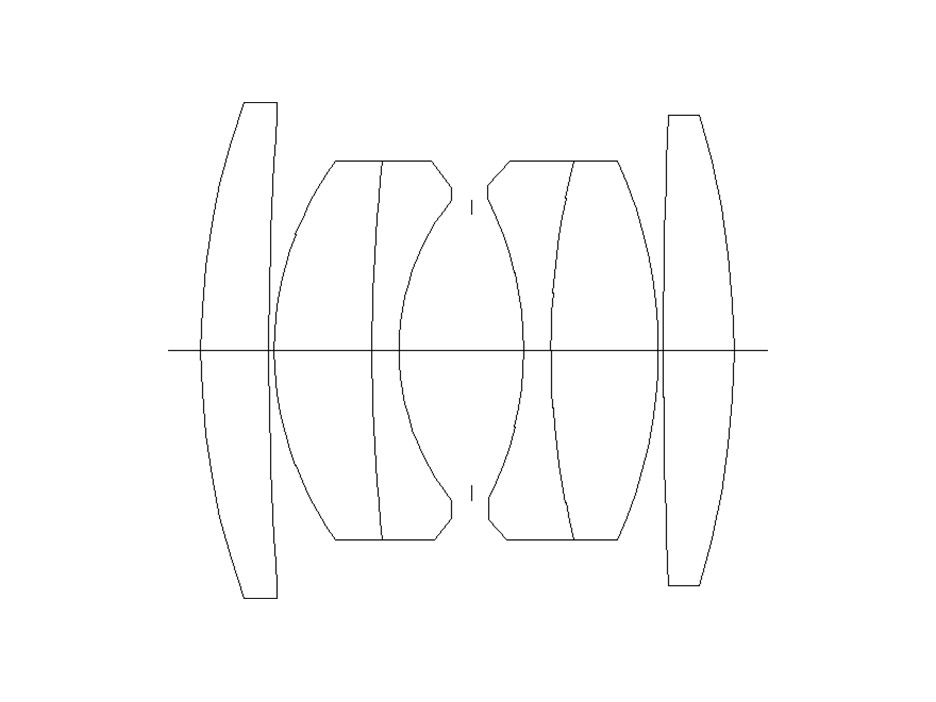

Autofocus: The N2020 uses Nikon’s first-generation autofocus module that contained 96 CCDs that focused on a subject in the precise center of the frame. For reference, Nikon’s later AM200 module used in the F4 and other cameras had 200 CCDs. The N2020 was designed to use Nikon’s “screw drive” AF and AF-D lenses, where a rather-noisy motor in the camera body focuses the lens. Today, autofocus lenses are now driven by motors in the lens itself powered by the camera body. The advantage of the later cameras is far less noise and vibration. The N2020’s autofocus, while very slow compared to modern cameras, is relatively capable and definitely works better in daylight than in low light. The N2020 can “focus lock” a point but half-depressing the shutter for reframing.

The N2020 has “single” and “continuous” autofocus modes. In “single” mode, the camera will not trigger the shutter until the subject is in focus. This mode permits one to focus lock a subject while halfway depressing the shutter button for reframing. The “continuous” mode was a primitive attempt at autofocus tracking. It does not work well at all.

When used with the SB-20 Speedlight flash’s assist lighting, the N2020’s low-light autofocus abilities vastly improve.

Focus Assist: For most manual focus Nikon lenses, the N2020 can use its autofocus sensor to “assist.” Through the arrows and circle at the bottom of the viewfinder, half-pressing the shutter button will activate the sensor. When the center circle turns “green” the lens is in focus. Focus assist is really a great feature, and it made its way into most subsequent higher-end Nikon film SLRs.

Exposure Modes: The N2020 has settings for three program modes, aperture priority, and manual operation. In program modes, the viewfinder will not display the selected aperture, only the shutter speed. “Program Hi” tells the camera to set a higher shutter speed and wider aperture. “Program Dual” will set the camera to “Program Hi” if the lens is 135mm or longer. If not, it will revert to regular “Program.” Aperture priority mode is straightforward. Manual permits the user the set the shutter speed on the camera dial, set the aperture on the lens, and the camera will let you know if the settings do not match the meter, by either blinking a shutter speed above or below the selected setting.

Auto Film Loading: The N2020 has the traditional swingback door with a film reminder window. Pull the film across the back and close the door. There is no automatic film rewind.

Underexposure Warning Alarm: The N2020 has a switch on the top that produce a loud beep if the shutter speed / aperture combination is not sufficient for the lighting conditions. Fortunately, you can turn this off.

Motor Drive: The N2020’s integrated motor drive is loud. In the most continuous mode, the camera can achieve up to 2.5 frames per second, which about on par with contemporary non-professional cameras. In normal ideal shooting conditions, the N2020 is good for about 1.5 – 2 frames per second.

Film Speed: The N2020 has a DX setting for coded film cassettes. Otherwise, the user can manually select any speed from 25 to 3200.

Exposure Compensation: On the ASA dial, there is a wheel for exposure compensation from -2 to +2. A separate adjacent button must be simultaneously pressed for the wheel to rotate.

Accessories

Focusing Screens: The standard “B” screen comes with the camera. Nikon also offered a “E” and “J” screen.

MB-3 AA Battery Pack: The stock N2020 uses 4 AAA batteries. The optional MB-3 module permitted the use of 4 AA batteries.

SB-20 Flash: The SB-20 is a really nice flash with a native bounce ability. Like other better Speedlights, in low light conditions, it will shoot a red light from the unit to assist the camera to focus in low light. The N2020 also has native TTL and auto flash ability with the older SB-15 and SB-16B units. The SB-18 could be used only in TTL or manual mode. With the SC-23 cord, the SB-14 and SB-11 could be used in TTL or manual mode. I am not sure if later Speedlights will work as my SB-30 would not couple with the camera.

Conclusions

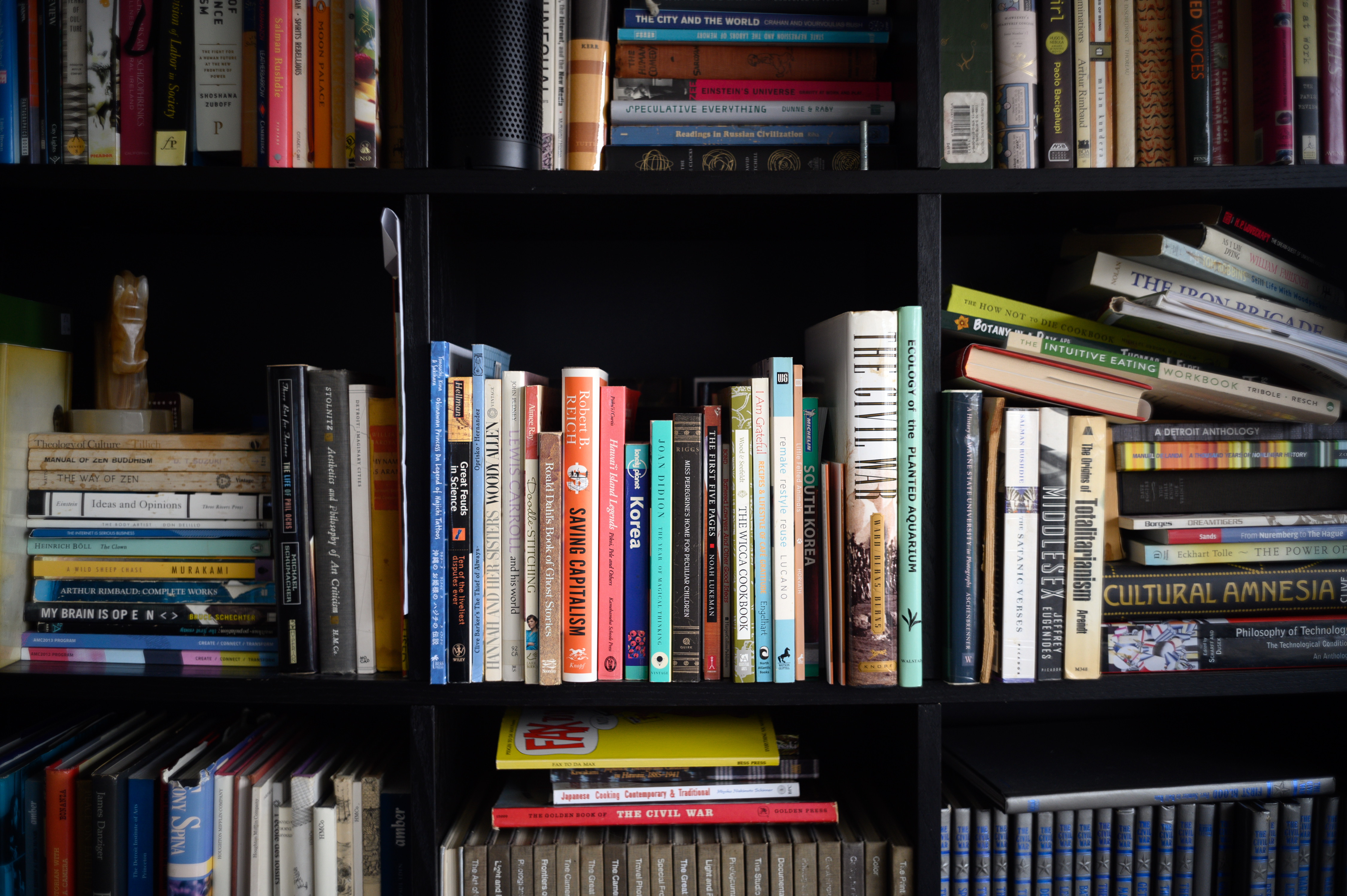

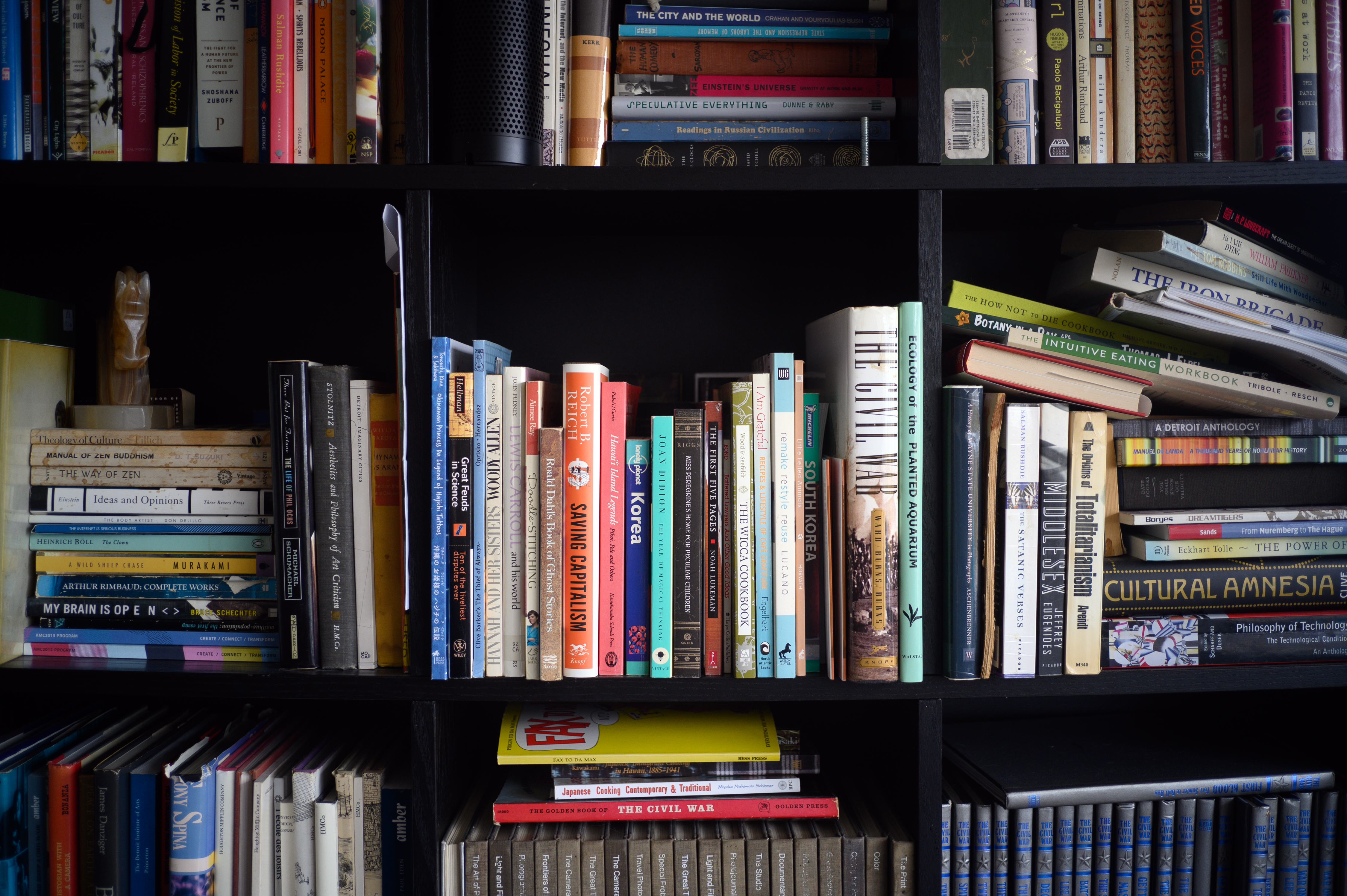

So what is a case for the N2020 today? While the camera is of average weight, with an average viewfinder, and has a very loud autofocus, shutter, and film advance, the N2020 was the last Nikon 35mm autofocus film body that retains a “classic” SLR look. The ability to use manual focus lenses in focus assist mode and AF/AF-D autofocus lenses makes it a more versatile platform than any of the consumer-oriented manual focus SLRs of the late 1970s and early 1980s. While the best Nikon camera of the 1980s is clearly the F4, the N2020 offers some of the same functionality in a much smaller package. However, with most Nikon AF film bodies being so cheap these days, if not the F4, F5, or F6, cameras like the N90s or the F100 simply blow the N2020 out of the water in all regards.