For many of us, a high-quality fixed lens 35mm film point-and-shoot is on the bucket list – a camera that we can carry around everywhere and about which we will not get too upset if it gets lost, broken, or stolen. In deciding a camera to acquire, for me there are really only two essential inquiries: (1) is the lens relatively fast and sharp? and (2) what is the probability that the camera actually autofocused on the right thing?

The Internet has already done a pretty good job of combing over the more popular, higher-end point-and-shoot models — like the Contax T series, the Yashica T4, the Nikon 35/28ti, and the Olympus Mju. However, having a small obsession with Konica-branded cameras (my father having purchased his Autoreflex T during Vietnam War-era service), I have been attempting to track down some of its lesser-known products to see if they are any good. While Konica products like the 1968 C35, the 1990s Big Mini series, and the 1993 Konica Hexar AF are generally well-known, 1980s-era Konica compacts not so much.

35mm cameras marketed during the 1970s and before required the user to know something about photography. The 1980s saw the rise of cameras that permitted users to take good photos without such knowledge. The advent of autofocusing made photography more accessible to the masses who were not keen on learning to use / lugging around heavy SLRs.

From the introduction of the C35 rangefinder in 1968 until the unveiling of the C35AF in 1977 (the first consumer autofocus camera), Konica was on top of the compact camera game (although its SLRs were always a step or two behind). The C35AF, while impressively beating all others to market, lacked a few essential features. It lacked a focus lock mechanism for off-center subjects. The viewfinder did not communicate to you what the camera was actually focusing on (although Konica expected you to look at a distance scale on the front of the camera to confirm) or whether you were too close to the subject. The absence of these basic indications will guarantee a certain number of misfocused shots on every roll.

Other manufacturers solved these problems before Konica did. In 1983, Nikon introduced its L35AF, which pretty much has all the features you would have wanted in a point-and-shoot from the mid-1980s — a 35/2.8 lens, an integrated motor and rewind drive, focus lock, an active autofocus mechanism, a viewfinder showing four separate autofocus distances, minimum focus to 0.8 meters, a backlight compensation switch, a thread for a screw-in 46mm filter, shutters speeds from 1/8 to 1/450, and on some models manually adjusted ISO settings from 50 to 1000. Canon, Chinon, Minolta, and Pentax all introduced similar products with more or less the same material features.

Falling far behind, in 1983, Konica introduced the last of its C35 series — the “AF3.” In 1984, Konica unveiled the very slick but overly-simple MG — a kind of automated, autofocus Olympus XA. Neither of these cameras was competitive from a features perspective. During this time, Konica also made simplified versions of the C35 with only zone or fixed focus in its “EF” series — and throwaway cameras like the Pop and the Tomato. Under no circumstances should you waste any money on the C35AF, C35AF2, the Pop, the Tomato, or any Konica camera with the EF designation. We are going to ignore the 1985 Konica MR70 (a twin focal length 38/3.2 + 70/5.6) compact camera because it is not in our “fixed lens” category here and because I have never seen one.

In 1986, Konica made a clean break from the C35 series with three brand-new cameras — called in export markets the MT-7, MT-9, and MT-11. The MT series represented the totality of the Konica fixed-lens point-and-shoot line until the introduction of the next-generation A4 in 1989, followed by the first of the “Big Mini” series in 1990.

All MT cameras share some basic features like an integrated motor drive, a built-in flash, and auto rewind. The MT-7 is an extremely basic camera with a fixed-focus lens that only focused down to 1.5m, one aperture per ISO value, a fixed shutter speed of 1/125, and a rather slow 36/4 lens. Think of the MT-7 as the next-generation Konica Pop. The MT-9 was more capable, with focusing down to 1.3 meters, a focus lock option, visual icons for the auto-focusing distance, an underexposure warning indicator, a “close-focus” flash option (discussed below), and a 35/3.5 lens.

The MT-11 was the flagship, sporting a slightly faster 35/2.8 Tessar-style lens. The MT-11 sold for about $150 in 1986, about the same price as the contemporary Nikon L35AF2, which translates roughly to $350 today. Konica would not produce another true point-and-shoot with a 2.8 lens until the 1990s Big Mini F.

Specifications

The MT-11 hits most, but not all, of the benchmarks established by the Nikon L35AF.

Lens: 35/2.8, 4 elements in 3 groups, Tessar-style

Motor Drive and Auto Rewind: Yes

Focus Lock: Yes, by slightly depressing the shutter

Autofocus Type: Passive

Autofocus Confirmation: Three LED indicators (close, near, and infinity)

Minimum Focus: 1.00 meter

LED Warning For Exceeding Minimum Focus Distance: Yes

LED Underexposure Warning: Yes

Backlight Compensation Switch: No.

Capability for Screw-In Filters: No.

Shutter Speeds: 1/4 to 1/500.

ISO Settings: DX Coded Only; No Manual Override; Defaults to ASA 100

Batteries: 2 x AA

Although a filter thread would have been nice, the biggest bummer on the list is the lack of manual override for ISO settings and the limited number of DX settings. I am still at a loss to understand why as the 1980s progressed, camera manufacturers moved to DX-coding only with only a limited range of ASA values. Seems like expanding the ISOs up to 1600 would have cost $0. But I guess if we are going to have this hypothetical debate, at a 1/500 top speed, 1600 speed film would have just overexposed all of your outdoor shots. And 800/1600 speed film may not have been a thing for regular people during the Ritz Camera era of photography.

The MT-11 has two features that the L35AF lacks: (1) automatic daylight fill flash; and (2) a bizarre flash-only close-up focusing mode that goes down to 0.45 meters (about 1.5 feet). Also interesting to note, Nikon’s subsequent L35AF2 (1985) and AF3 (1987) cameras actually had less functionality and manual control than the original L35AF.

Operation

Photos may not do the MT-11 justice. It is a really handsome, well-designed camera. Although its shell is hard plastic, there is nothing flimsy about it. Everything is intuitive. There are only a total of five buttons and switches — shutter (top), self-timer (top), flash (front), on switch (front), and rewind (bottom). The lens is protected by an door whose opening also acts as the camera’s “on” switch and prevents any shots while closed.

Although lacking in any override, the camera functions well. As stated above, the most frustrating part of point-and-shoots, unlike SLRs and rangefinders, is that you often never can be sure what the camera just focused on. The MT-11 has three autofocus confirmation lights in the viewfinder. Half depress the shutter, and you will see either a person (close), or a group of people (near), or a mountain (infinity). Depressing the shutter halfway locks the focus point. A blinking person means you are too close to the subject. A flash light will blink in the viewfinder as an underexposure warning. You can force a shot with no flash on the MT-11 by simply not activating it. Underexposure will most likely default the camera to its wide open settings (1/4 at f/2.8, I believe).

The autofocus mechanism is “passive,” and the lens does not physically move until after the shutter is tripped. The pre-shot autofocusing is completely silent. I am almost positive that MT-11 operates in “steps” to correspond to distances and aperture combinations — it is just unclear how many there are. There is a typical brief shutter lag as in all cameras of this class and the motor drive is a bit noisy (noisier than the MG). In daily practice, the autofocus works “pretty well” but you will often need to “try again” if the camera indicates “far away” when your subject should be “close.” Also, the autofocus does seem to have occasional problems focusing on uniformly-colored subjects (either light or dark). This reveals a limitation of a “passive” autofocus system that requires the scene to have at least some contrast.

The light meter appears to be somewhat primitive and can be fooled by strong backlight in a scene. If your subject is close and backlit, consider using the flash. Otherwise, just be careful.

Like in most of its advanced compact cameras since the C35, the MT-11 uses a “Tessar” lens — 4 elements in 3 groups. It is likely that the MT-11’s lens is a derivative of the C35’s optics, but that is not clear from any extant literature. The Tessar is a simple, effective design that is easy to mass-produce and can be found in almost every higher-end point-and-shoot made in Japan during the 1980s and into the 1990s. Do not expect Leica-like performance from the humble 35/2.8. It is a capable lens for your standard 1980s 4x6s and 5x7s. For internet purposes, it works just fine.

Feature No. 1: Daylight Ambient Flash

Ever since the introduction of the Konica S3 in 1973, Konica had been firmly committed to the concept of daylight fill flash. Almost all of Konica’s point-and-shoots were programmed to shoot daylight flash. (At the same time, Konica never produced an automatic daylight fill flash system for any of its SLRs). The MT-11 is no exception. The operation is simple — just turn on the flash and take a daylight photograph. I am not sure exactly the method used, but I imagine that it is a descendant of the Konica S3’s system. The built-in flash syncs at full power at all shutter speeds. The autofocus sensor sends the distance information to the camera which then adjusts the aperture and shutter speed accordingly. Fill flash from point-and-shoots is not often flattering, so consider finding some material with which to attempt to diffuse the flash a bit.

Feature No. 2: Close-Up Flash Focusing

Certainly the oddest feature on the MT-11 is this “close-up flash mode” which permits you, only with the flash on, to take a photo at a distance down to 0.45 meters (about 1.5 feet). I am not quite sure what this mode is attempting to accomplish. In any event, if you press and hold in the lever next to the lens the flash pops up and then angles. You will see that the autofocus LED will no longer flash when you are closer than 1 meter to the autofocus point. However, in this mode, the camera will not tell you if you get closer than 0.45 meters to the subject. For those who do not carry a ruler around, for a close-up subject, the idea would be to find the 1 meter minimum focusing mark and then “lean in” towards the subject slightly, but not more than 0.55 meters inwards.

Should You Buy One?

Once I started looking for an MT-11, it took quite a while to locate one for a decent price and in good condition. It is not clear whether its apparent rarity is because it never sold well in the USA, because they are sitting in people’s basements and attics, or because a strategic stockpile of them is hiding in resale shops across the country.

I wholeheartedly agree with the Internet that if you are going to acquire a film point-and-shoot camera you should go straight for the good ones. To me, the point of a point-and-shoot camera is to take it with you everywhere and not be out a rent or mortgage payment if something befalls it. Because the MT-11 checks both essential boxes — it has a good and fast lens, and it minimizes the possibility for user autofocus error — I say that you cannot go wrong with it. Other cameras to consider in the mid-1980s class would be the Nikon L35AF (the original one with the ASA up to 1000, and not the AF2 or AF3), the Chinon 35FA Super, the Pentax PC35AF, or the Minolta AF-C (no built-in motor drive). Of these other options, the L35AF still has the most features.

Sample Photos

Here are a few sample photos taken on Kodak Portra 400. As you can see, the MT-11 is more than capable as a snapshot camera (assuming you nail the focus).

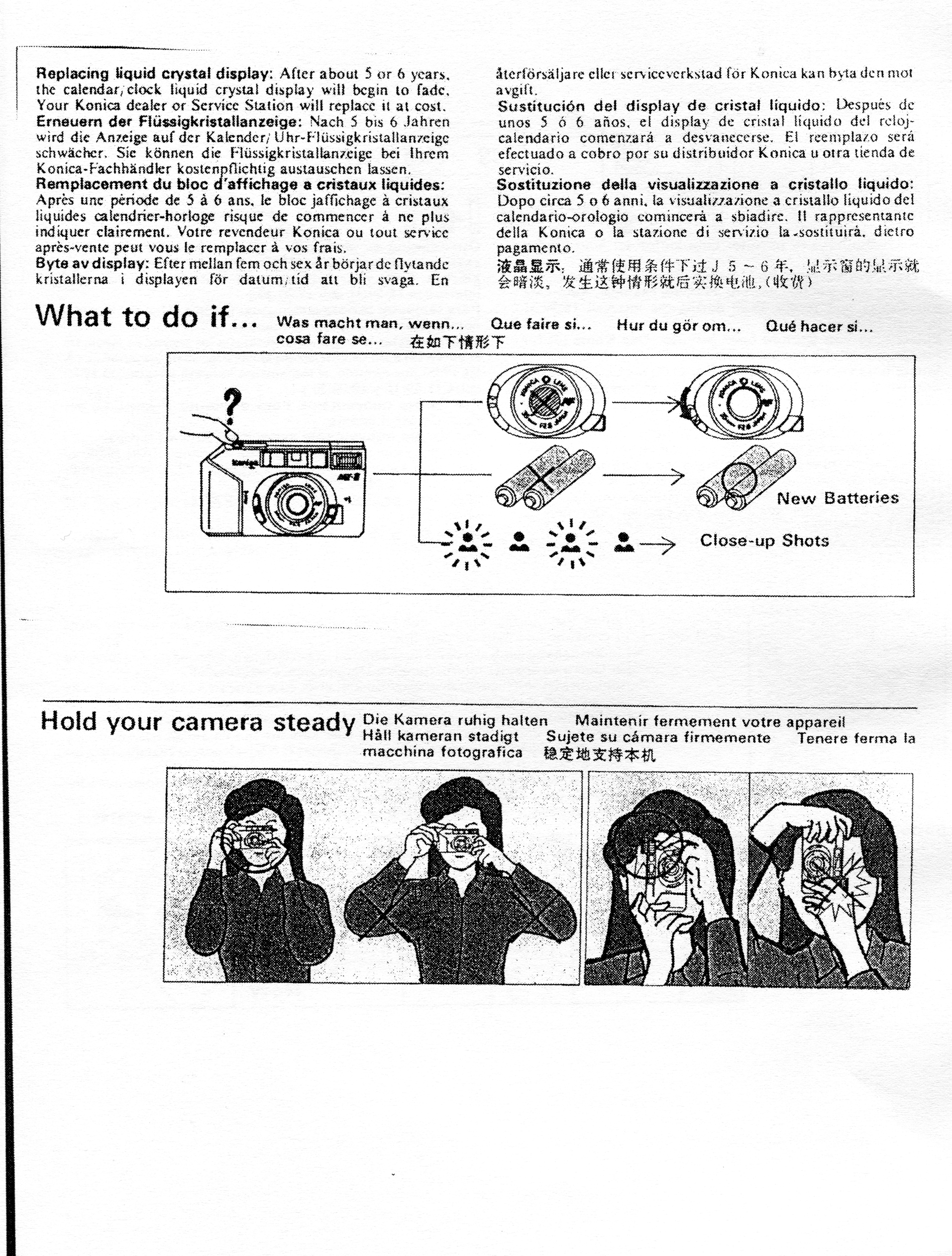

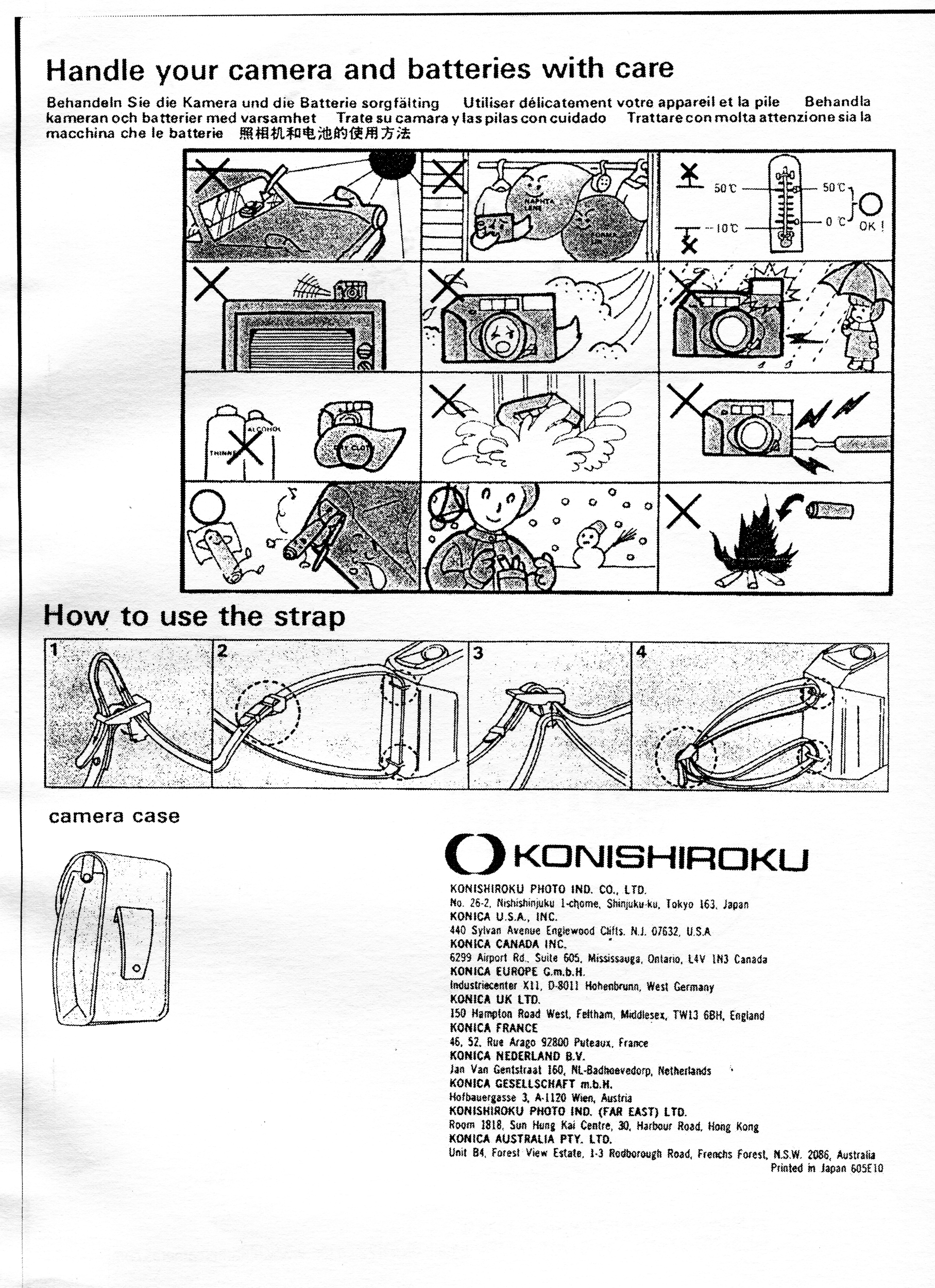

Instruction Manual

Because the MT-11 instruction manual is otherwise unavailable on the Internet, here you go.

Just wanted to say thanks so much for this. So useful. I recently bought a pricey Mju II that the seller said worked fine, but unfortunately, doesn’t. I found a cheap(er) one of these listed because the grip is peeling. I think I’m going to give it a go.

Thank you so much for this excellent write-up on the MT-11. I first heard of this camera from an Instagram post by the Japanese photographer Hiroyoshi Yamazaki, whose new book “Smell on the Street” includes at least one photo shot with this camera. Of the photo in question he writes:

“This photo was taken with a Konica MT-11 compact camera. This camera has a function that allows you to narrow down the aperture when shooting with the built-in flash. Being able to shoot in sync during the day created a surreal atmosphere.”

I’m guessing that’s the “close up flash mode” you describe in your essay, though I’m not sure. You can see the photo here: https://www.instagram.com/p/CnqGCSxylo5/

Now I’m curious enough about the MT-11 that I’ve been trying to find one — not an easy camera to find so far (though there are many MT-100s available). I don’t have a deep need for it, as I already own a Yashica T4, (which I’ve had since 1993 but which I only dug out from a drawer recently after going digital in 2004). Ritz Camera was my most frequent destination for developing and that fit my level of skill and knowledge.

Thanks again for the entertaining and informative essay.

I wouldn’t say to entirely disregard Konica’s zone focus cameras! While the EF3 is quite prone to light leaks, it has a lovely 5 elements in 4 groups (possibly Sonnar-style?) f2.8 lens. I’d take it over any of the late 80s AF point-and-shoots any day just because it’s a lot faster in operation.