To Americans, “Okinawa” usually conjures images of a fierce two-month battle in 1945 against entrenched and determined forces of Imperial Japan. The battle killed half of the native Okinawans, nearly 150,000 of a pre-war population of approximately 300,000. The fighting and bombing destroyed virtually every building, historical site, and record. A little-known fact is that the United States annexed Okinawa after the battle, installing a military government that lasted until a 1972 democratic referendum that voted for reunification with Japan. Okinawa still houses large, sprawling military bases for both forces of the United States and Japan.

Although an integral part of Japan today, Okinawa was not traditionally part of it. In fact, the islands were known as “Ryukyu” to the Chinese as early as the 8th century ACE. “Okinawa” is the Japanese term. Sitting in an archipelago stretching to Japan to the north and Taiwan to the southwest, Okinawa operated an semi-independent kingdom throughout what the West considers to be the Middle Ages.

Before the 17th century, Okinawa existed as an independent kingdom and nominal “vassal state” of the Kingdom of China. However, China only imposed tribute and loyalty obligations on their vassal states. Although Okinawa had its own language and indigenous culture, like most other neighboring peoples, Chinese cultural influence was dominant. During this period, Okinawa enjoyed some success and autonomy by acting as sort of a “neutral” trading ground among the kingdoms of China, Korea, and Japan.

In 1609, the Japanese Shogunate invaded and conquered Okinawa. Henceforth, Okinawa operated as both a kind of vassal state of both China and Japan. As the story goes, because Japan outlawed civilian weapon ownership, Okinawans subsequently invented a martial art known as “karate.” In 1879, Meiji Japan formally annexed Okinawa. However, despite pressure by the Japanese at this time to assimilate the Okinawans and suppress local language and customs, encourage them to adopt Japanese versions of their name, and to conscript them into the military, Okinawans retained a strong independent identity, even up through the 1945 battle.

Because of the significant need for laborers for the sugar and pineapple plantations, the Kingdom of Hawai’i imported a large number of Japanese, Chinese, Korean, and Filipinos laborers during the late 19th century. However, the international conglomerates running Hawai’i agriculture treated Asian laborers little better than slaves. “Pidgin,” which still can be heard in Hawai’i, was a dialect developed by Asian and native Hawai’ian laborers combining words from multiple languages to communicate with each other and with their overlords. In a little-known, but impressive, act, after the United States formally annexed Hawai’i in 1898, the Hawai’i Organic Act was passed in 1900, which invalidated the oppressive labor contracts imposed upon immigrant and native laborers and forced renegotiation of their terms. Also around 1900, significant numbers of Okinawans began moving to Hawai’i to take advantage of the booming opportunities in agriculture. However, in 1924, the United States halted further East Asian immigration. Americans of Okinawan descent served with distinction with many military units throughout the war.

To this day, because of the late 19th and early 20th century immigration, Hawai’i and Okinawa share a strong cultural connection. In fact, in the aftermath of the 1945 battle, Hawai’ians organized a humanitarian relief effort to aid the local population. In Okinawa today, you can see people wearing Hawai’ian shirts. More info on the history of the deep bonds between Okinawa and Hawai’i can be found here.

In 1945, the United States, obviously knowing very little about Okinawa, did not appreciate the fact that many Okinawans still regarded the Japanese as outsiders and colonizers. As a result, the battle was unnecessarily vicious and destructive. The United States surrounded the isolated island with a large armada. And for two months, the military destroyed everything on the island.

After the war, the United States occupied and annexed the island. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Okinawans, resenting the large military presence, starting demanding an end to the occupation. Resentment only grew with the United States using Okinawa as a staging ground for the bombing of Vietnam. The protests ultimately culminated in a referendum in 1972 which ended American military rule and reunited the island with Japan. However, the militaries of United States and Japan continue to occupy a significant portion of the main island. Given their resentment at the occasional serious crimes committed by military personnel, and their desire not to be a military target again in a future war, most Okinawans still wish to see the departure of all military personnel from the island.

After reunification, Japan poured a significant amount of resources into the island. Today, the population of Okinawa is about 1.4 million people, five times its pre-war population. The cities, nestled in the valleys between principal hills, are densely populated, with gridlock traffic during the work day. Small farms dot the landscape in between the cities and hillsides.

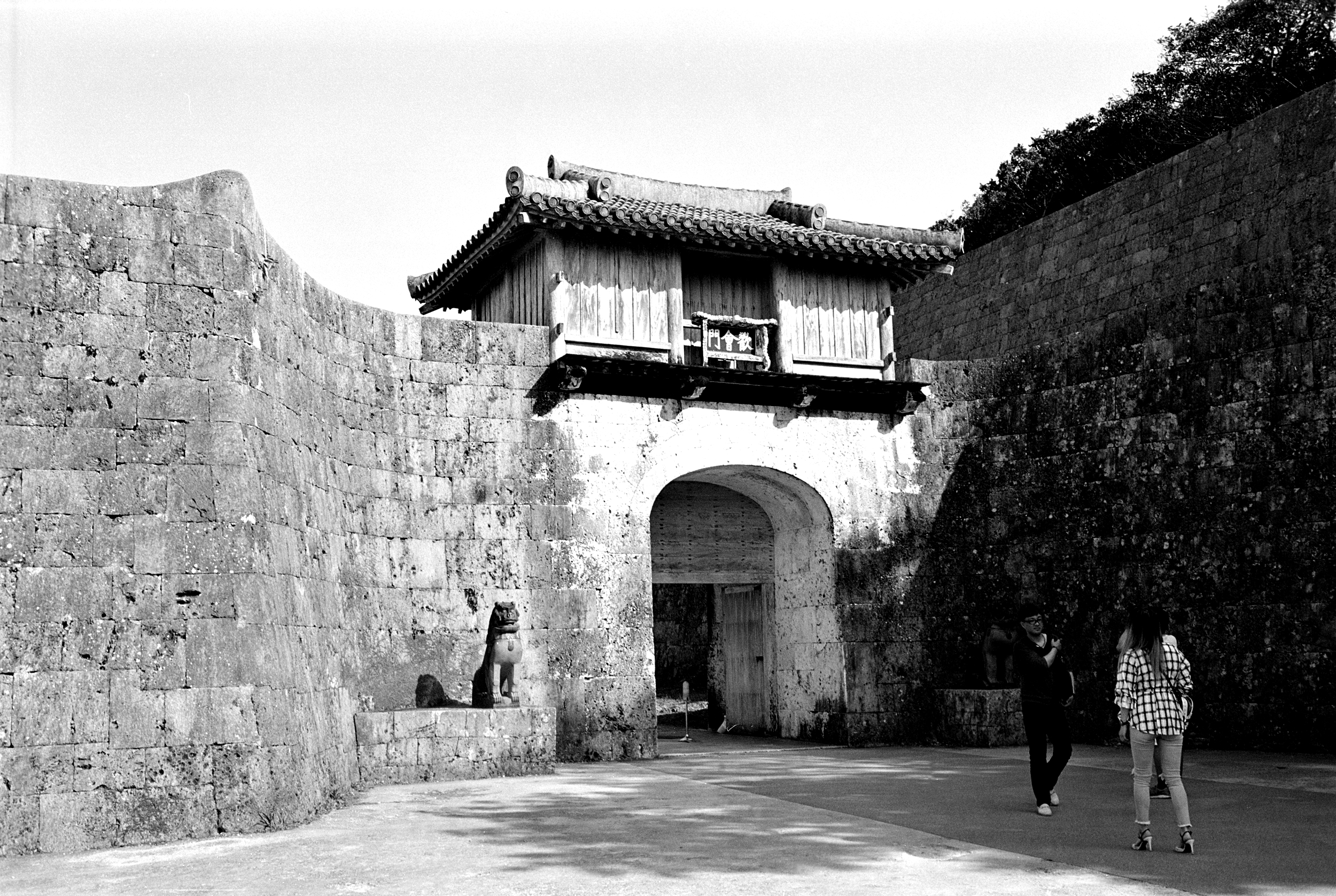

The 1945 battle pretty much erased much of the physical evidence of Okinawa’s history, destroying its cities, its unique family tombs that had been carved into hillsides, its palace, and its historical and government records. What did survive, in part, were some of its stone hilltop 14th and 15th century “Gusukus” (meaning “castle” or “fortress” to some, “holy place” to others, depending on how one interprets Chinese characters). Although many of the gusukus were damaged by military shelling and bombing during the battle (as the Japanese used many of them as artillery positions), significant post-war efforts have restored many of them.

Here are some touristy travel shots were taken with a Konica TC-X with my Dad’s old 35/2.8 Hexanon (borrowed from my brother). I liked this lens so much that after this trip I located and purchased the 35/2 Hexanon. The color photos were taken with a Fuji X20 digital camera.

The Gusukus

During the 14th and 15th centuries, Okinawa was divided into several smaller principalities. During this period, local leaders built large stone castles on hilltops overlooking the sea and the land below. The ruins of the gusukus dominate the landscape of Okinawa from north to south. Scholarship has revealed that even after these installations fell into disrepair with the Shogunate invasion, local religious rites were carried out on the ruins of these sites. Apparently, both ancient Roman and Ottoman currency have been found at these sites — a testament to Okinawa’s importance as a center of trade and cultural exchange.

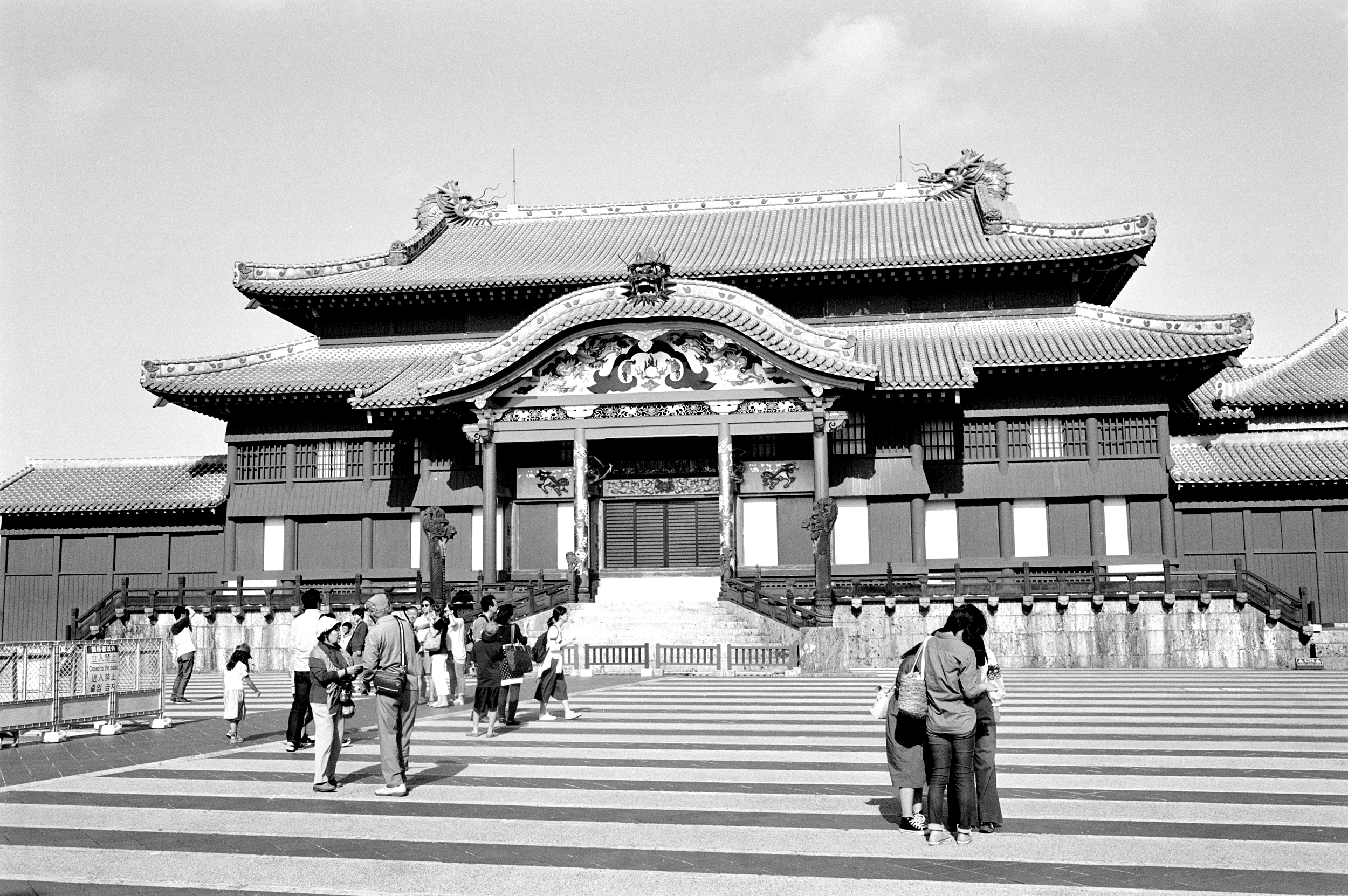

Shuri Castle

This 14th century edifice was completely destroyed during 1945. Since the unification of the Ryukyu Kingdom, it was its political, economic, and cultural hub. Built on a commanding hill, its architecture is distinctly Chinese. In the 1920s, a Japanese architect assisted in the castle’s restoration, and it was declared a “national treasure.” In 1945, shelling from the battleship U.S.S. Mississippi destroyed all of palace buildings. Starting in 1992, Shuri Castle was reconstructed according to old plans and photos. It is pretty magnificent.

“Turtle Back” Tombs

An ancient Okinawan tradition included establishing an extended family tomb in the side of a hill. These tombs are scattered throughout the island. The space doubled as an area to pay respects to one’s ancestors. Many of these tombs were obliterated during 1945, with some being rebuilt after the war. Okinawans tell heartbreaking tales of families hiding out in the tombs during the bombing of the island. However, the tradition remains alive as “new” traditional tombs are still being built today.

World War II Stuff

Unfortunately, the 1945 battle imprinted a lasting mark on both the people and physical landscape of the island. Around the time of reunification with Japan in 1972, Okinawa began construction of its “Peace Memorial Park” on the southern part of the island where the Japanese made their last stand and where General Mitsuri Ushijima, who led what many military historians consider a skillful defense of the island given the massive inferiority of his forces, committed suicide when the battle was lost.

The Peace Memorial Park contains freestanding monuments listing by name the roughly 240,000 people who died in the battle — Okinawans, Japanese, Koreans, and the Allied Forces. The Koreans who fought with the Japanese have their own monument. While there, we witnessed Japanese naval personnel visiting the Park.

Small portions of the intricate series of tunnels dug by the Imperial Japanese Army are open for view. In these tunnels, one gets the sense of the desperation and futility of the fight. Besides the military conflagration, the ultimate tragedy were the deaths of so many Okinawans, pressed into service by the army to fight a hopeless battle.