Today, Leica, Zeiss, and Voigtlander continue to produce fantastic 50mm rangefinder lenses, and there is little doubt that the current generation is generally far better than anything that came before. While certain people will always desire the absolute newest and most expensive lenses, older lenses remain capable of taking great photos both on film and digital. In this piece, we are going to compare some older and affordable “fast” 50mm rangefinder lenses to attempt to ascertain their relative strengths and weaknesses: (1) the 1948 Jupiter-3 50/1.5; (2) the 1959 Canon 50/1.4 II; and (3) the 1962/2000 Nikkor-S 50/1.4. Comparing lenses under the same conditions can often tell us much more than looking at a single lens in a vacuum.

Jupiter-3 50/1.5 (1948)

Specifications

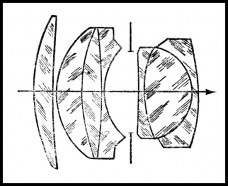

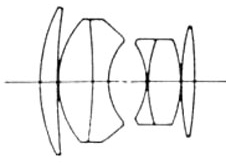

Optical Design: 7 elements in 3 groups.

Minimum Focusing Distance: 1.00m

Aperture: f/1.5 – f/22 (continuous, no click)

Mount: Leica Screw Mount (M39)

Filter Size: 40.5mm

Weight: 140g

As the familiar story goes, as part of the “reparations” exacted from Germany after the war, the Soviet Union appropriated much of Zeiss’ intellectual and real property. Before and during the war, Zeiss had produced its fast and famous 50/1.5 “Sonnar” lens in Contax rangefinder mount with a much smaller number manufactured in Leica screw mount. After the war, Zeiss split into separate West German and East German (Jena) entities. Zeiss Jena continued to produce the 50/1.5 Sonnar in Contax rangefinder mount after the war. The Sonnar also became the basis of many longer SLR lenses designed by both West and East German Zeiss entities.

By 1947, the Soviets has prototyped their own Sonnar copy. By 1948, it was in production. Christened the “Jupiter-3,” the Soviets, in different factories over the years, produced the lens in M39 for its “Zorki” cameras and in Contax rangefinder mount for its “Kiev” cameras. With periodic variations in barrel and exterior design over the years, the Jupiter-3s were produced well into the 1980s. Lomography even managed to re-pop these lenses for a time as the “Jupiter-3+, with the newer version focusing down to 0.7m and having multicoated glass. Unfortunately, these are no longer being produced.

There has been much debate whether the Jupiter-3 in M39 were actually collimated from the factory in precise Leica specification. The consensus seems to be that most Jupiter-3s in M39 were not. If you are planning on using a Jupiter-3 on a Leica M39 or M rangefinder camera, and the history of your particular example is unknown or in doubt, you should strongly consider retaining an experienced camera repairperson who can properly adjust your Jupiter-3. The discontinued Jupiter-3+s are properly collimated for Leica out of the box.

By reputation, the Jupiter-3 is not considered to have substantially improved upon the original Sonnar’s performance. It was always a single coated optic and quality control in the various Soviet factories that produced them was not always the best. However, the Jupiter-3 has plenty of fans as the lens has traditionally been the cheapest “copy” of the Sonnar template and its wide-open performance can be used to good effect.

The first two numbers of the serial number of Soviet lenses typically indicate their year of production. This black paint example (seemingly rare for the period) appears to be from 1962 and has a purplish lens coating.

Canon 50/1.4 Type II (1959)

Specifications

Optical Design: 6 elements in 4 groups

Minimum Focusing Distance: 1.00m

Aperture: f/1.4 to 22 (full click stops)

Mount: Leica Screw Mount

Filter Size: 48mm

Weight: 246g

In 1939, Canon produced the “Model J,” a screw-mount 35mm rangefinder camera However, the J’s lens mount was not the same thread as Leica. Because the war seriously disrupted Japan’s domestic camera industry, it was not until afterwards that Canon was able to launch a series of admirable and well-selling M39-mount lenses and cameras.

In the mid-1950s race to produce “super fast” 50mm lenses, Canon introduced its famous 50/1.2 in 1956 — the fastest commercially-available lens then produced in M39. The 50/1.2 is a very cool lens — having owned one many years ago, our impression was that its performance at f/1.2 and f/1.4 was not great.

In 1957, Canon followed the 1.2 with the “Type 1” 50/1.4. Canon slightly tweaked the 1.4 with the “Type 2” in 1959. The Canon 50/1.4 has always enjoyed a good reputation as a solid performer with “acceptable” performance at f/1.4 with much improved performance at f/2 and smaller. The functional downsides include a minimum focus of only 1.00m and a rather stiff aperture ring. It was an extremely popular lens that came as an option on numerous Canon rangefinders. Today, they are rather cheap and plentiful.

Olympic/Millennium Nikkor-S 50/1.4 (1962 & 2000)

Specifications

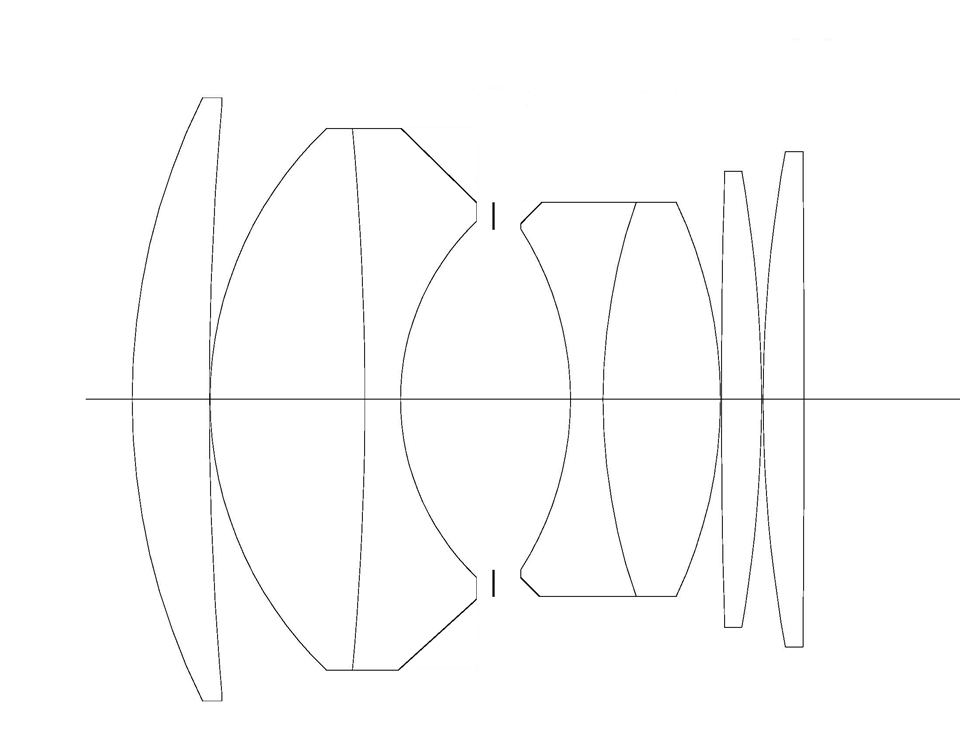

Optical Design: 7 elements in 5 groups

Minimum Focusing Distance: 0.9m

Aperture: f/1.4 to 16

Mount: Nikon S

Filter Size: 43mm

Weight: 178g

Nikon gained a reputation in the late 1940s and early 1950s for the production of a series of excellent rangefinder lenses made in both its own “S Mount” and in M39. One of its most popular lenses of the 1950s was the single-coated Nikkor-S.C. 50/1.4, a design based upon the Sonnar template, but not really a “copy” of the original 50mm f/1.5 Zeiss Contax lens.

By the late 1950s, the landscape had changed. The Sonnar was out, and the Gauss was in. In 1962, Nikon released its Nikkor-S 50/1.4 lens for its F SLR. Around the same time, Nikon redesigned its 50/1.4 rangefinder lens, in anticipation for a “re-release” of an black-paint Nikon S3 rangefinder. This latter variation of the 50/1.4 is now commonly known as the “Olympic” Nikkor — as it was advertised in conjunction with the 1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo. The design was closer to that of the Nikkor-S SLR lens than either the contemporary Canon or Leica Summicron design.

Fast forward to 2000 when Nikon embarked on an ambitious project to recreate from the ground up its iconic 1958 S3 rangefinder. The story of the project is fascinating and worth a read. Nikon recreated its “Olympic” Nikkor but with multi-coated (instead of the original single coated) optics and a standard modern filter size (43mm x .75). After a limited run, Nikon ended production of the new S3 in 2002. The “Millennium” Nikkor 50/1.4 is a little difficult to find as a standalone lens because it was sold as a set with the S3. Many people buy the set, put the S3 back in its box, and use the 50/1.4. Of course, with the Amedeo adapter, the Nikkor can be fully functional on your Leica M camera.

Comparisons

We are going to take these three lenses plus a Konica M-Hexanon 50/2 and take three series of shots on a Nikon Z6 mirrorless camera with all automatic corrections turned off. We are most interested in evaluating these lenses for sharpness, distortion, coma, and flare control. Click on an image below for a 4500 pixel version.

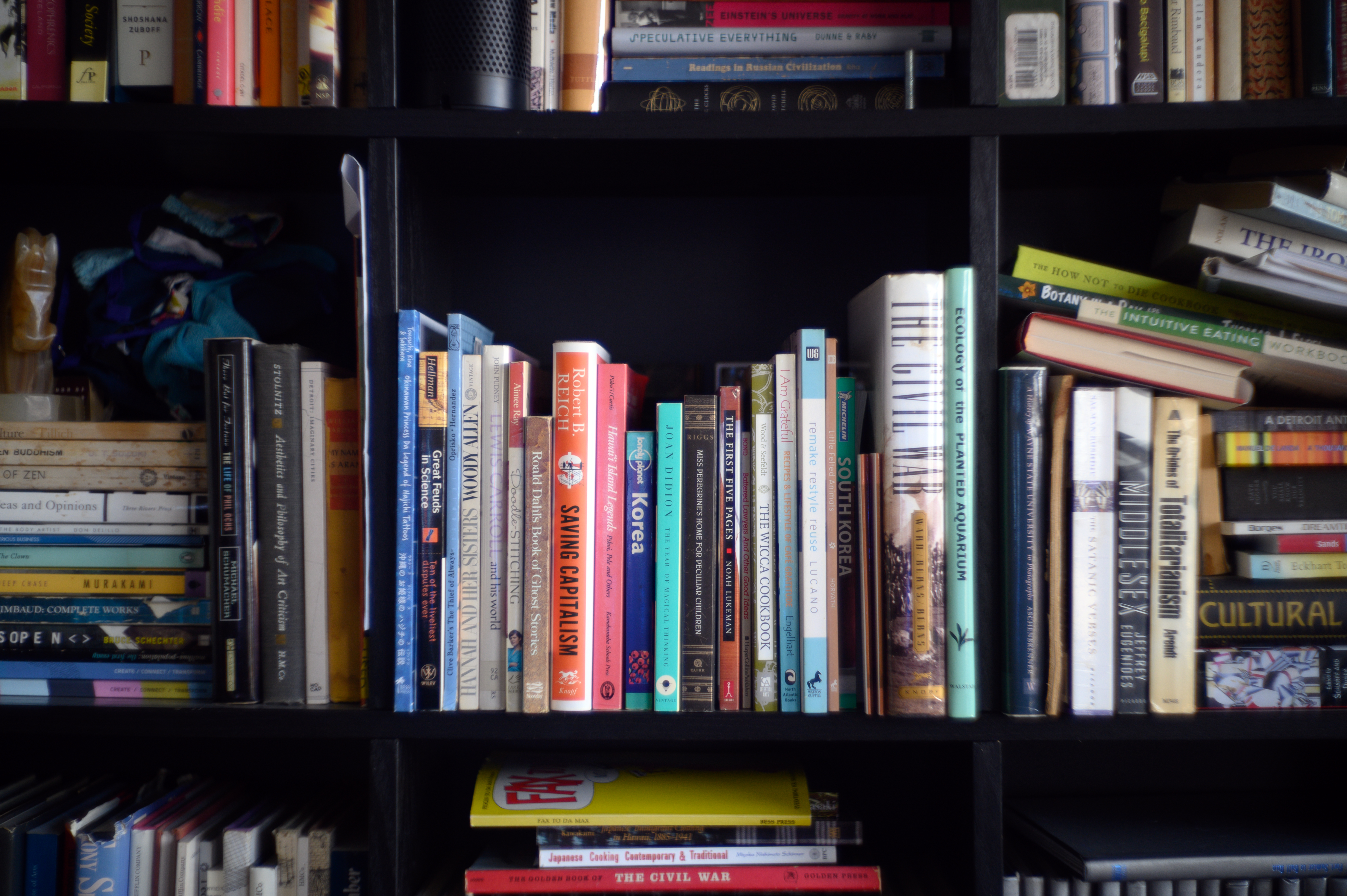

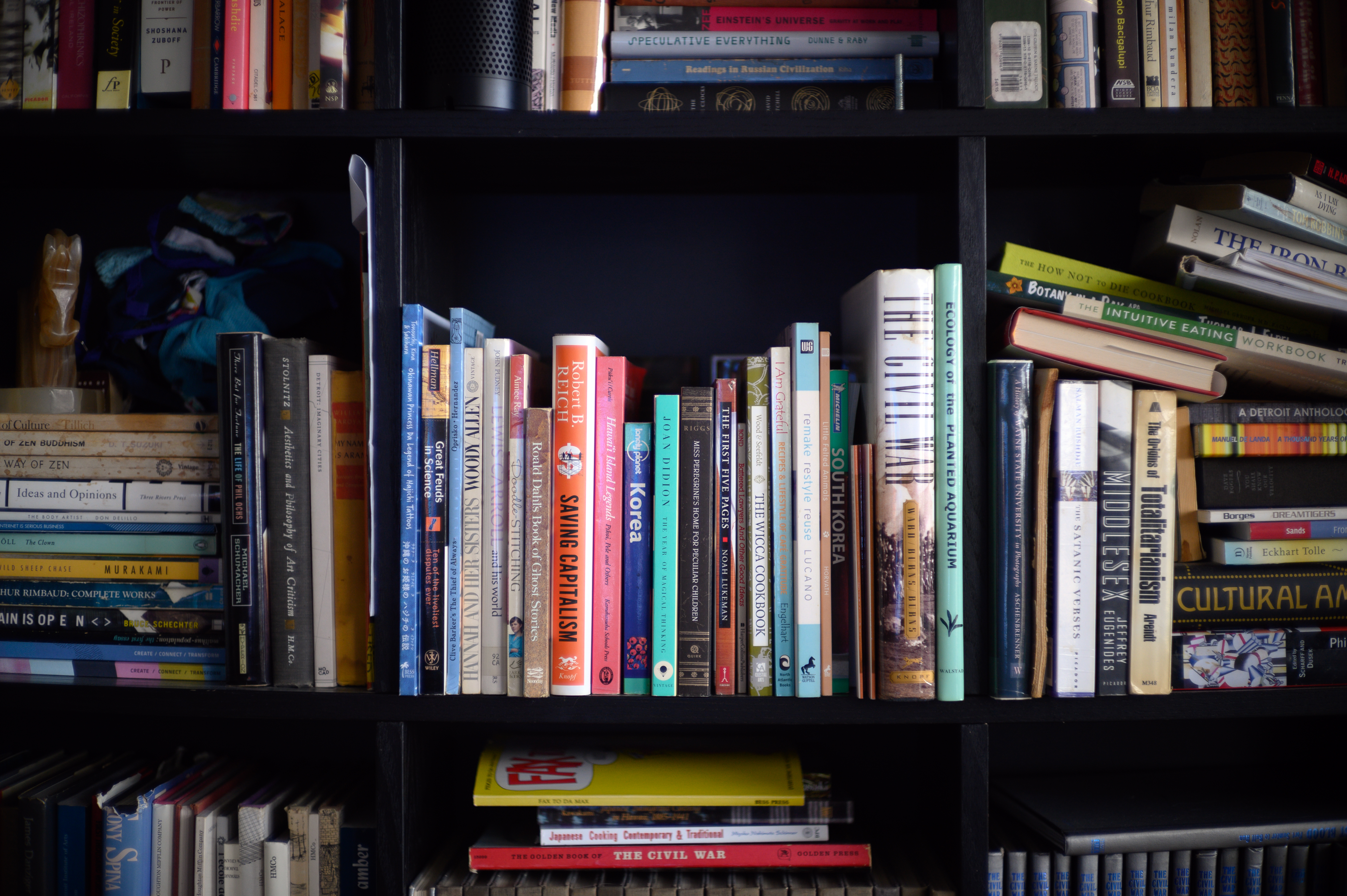

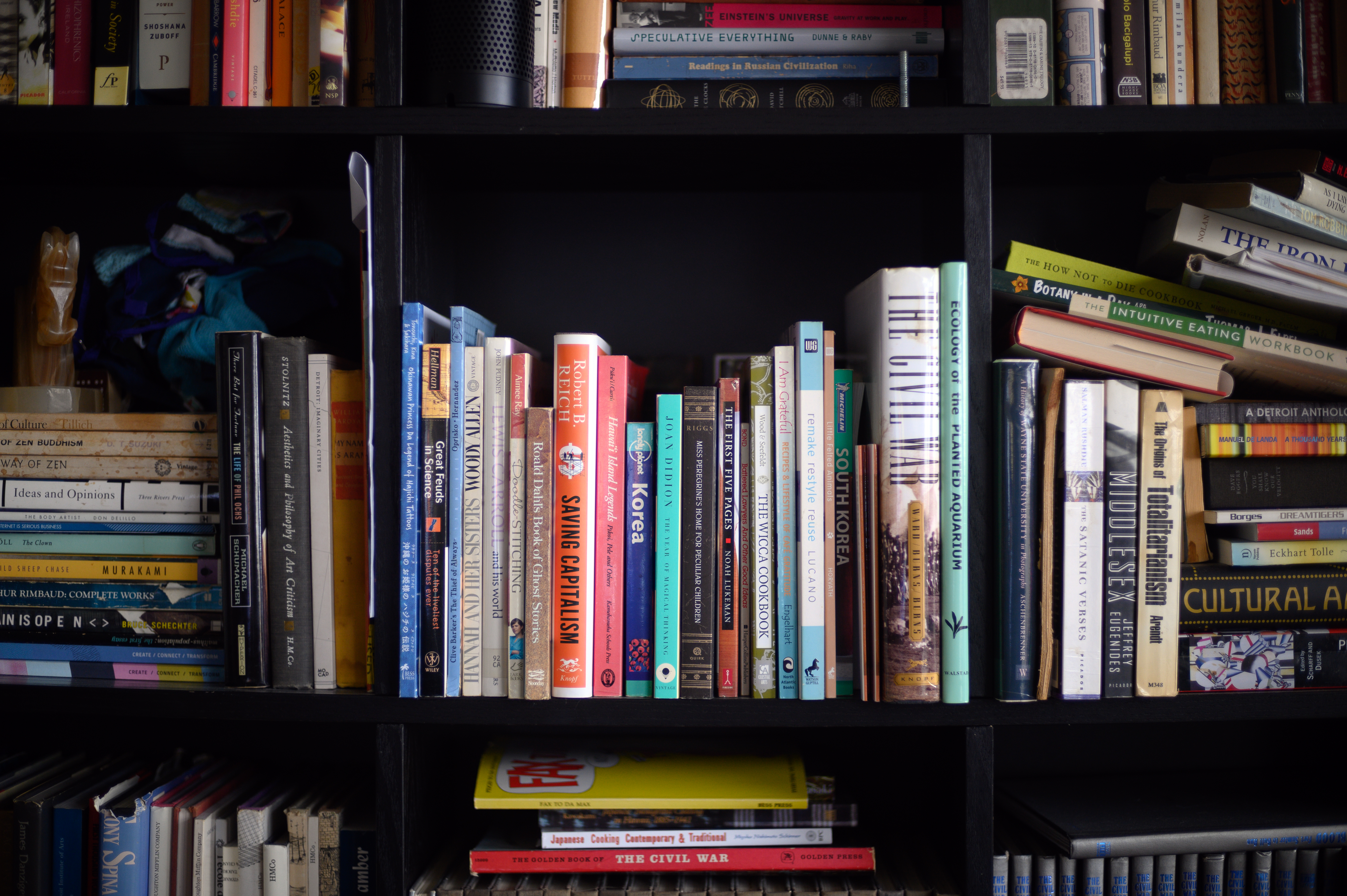

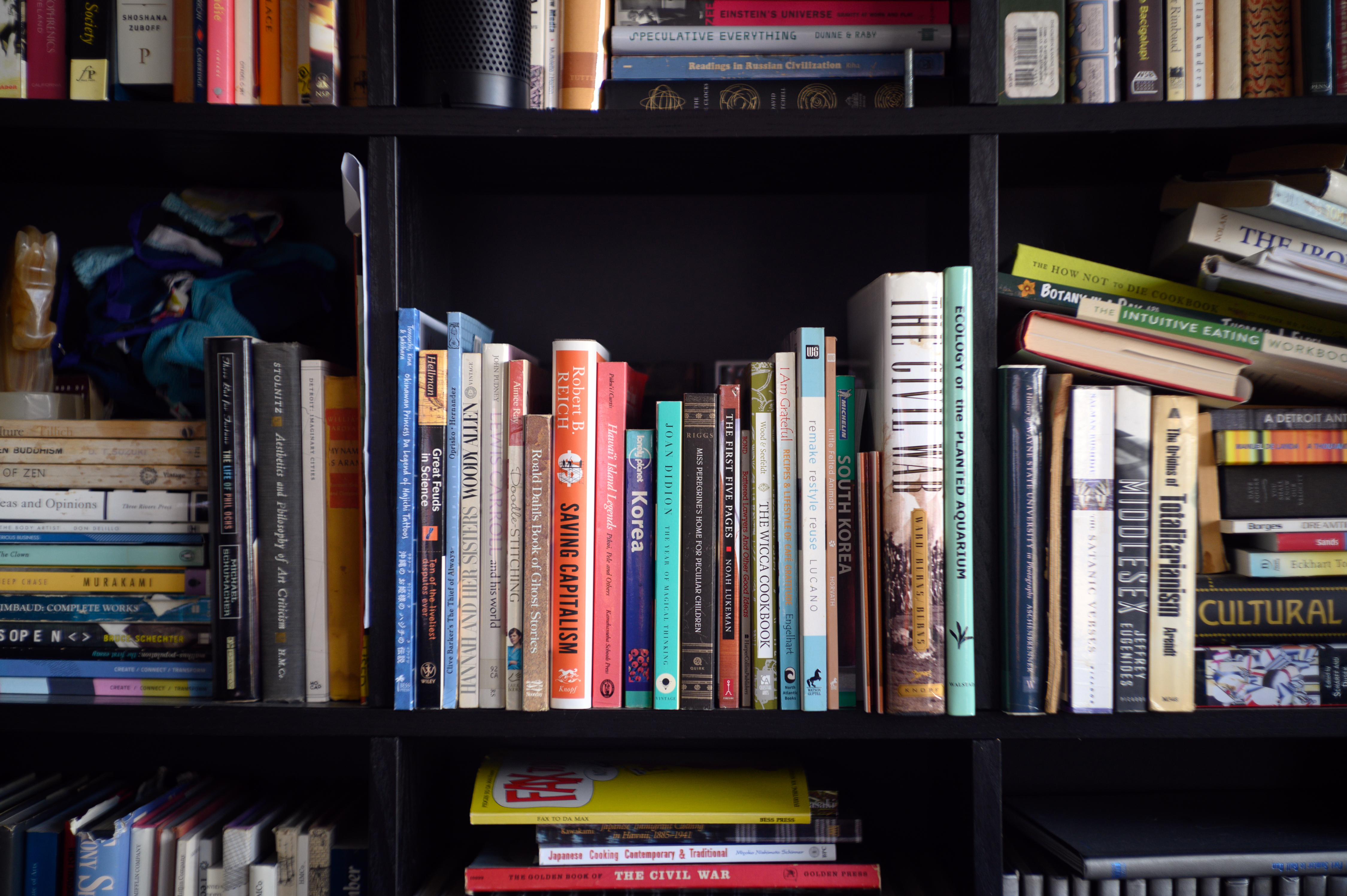

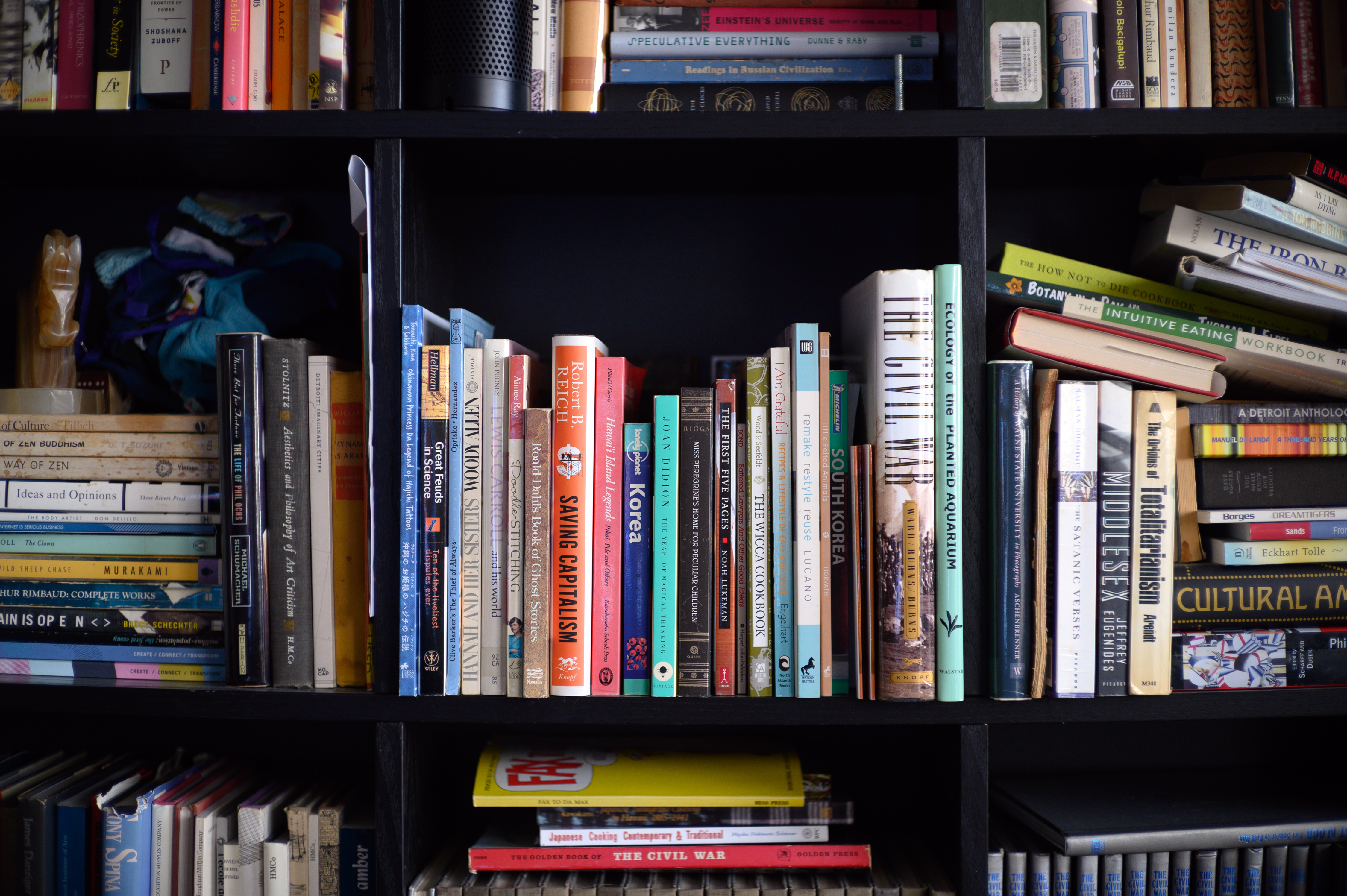

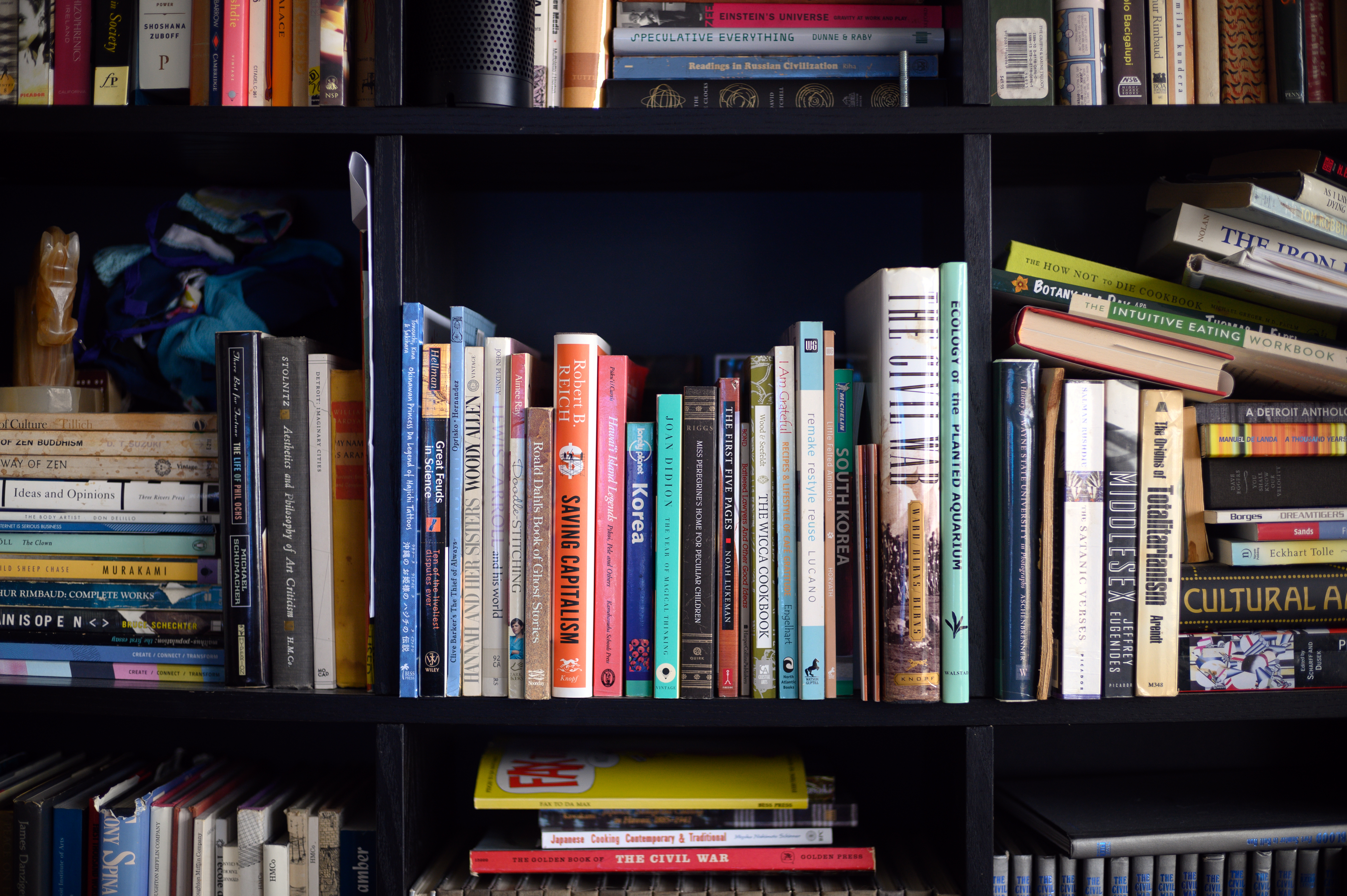

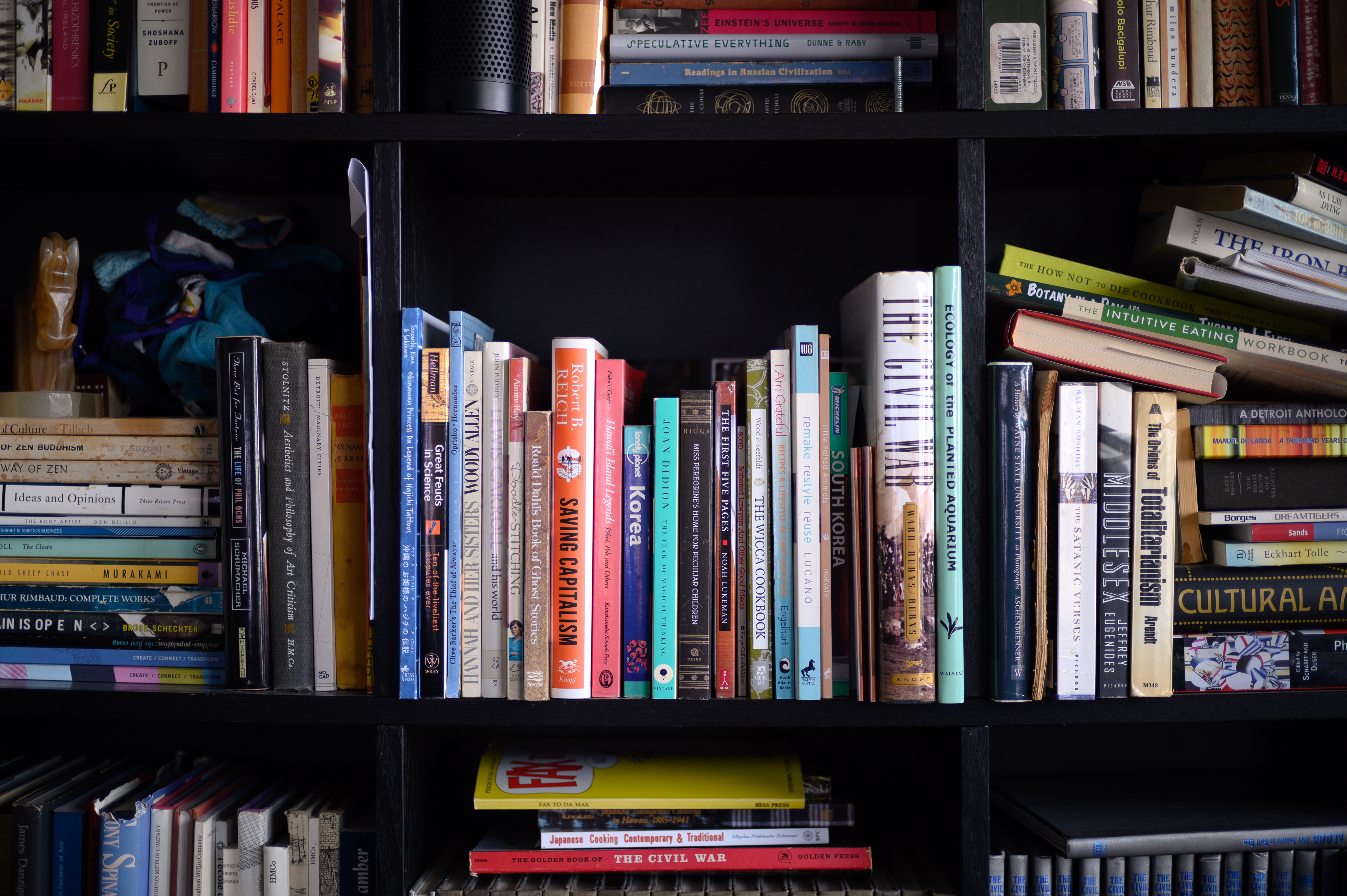

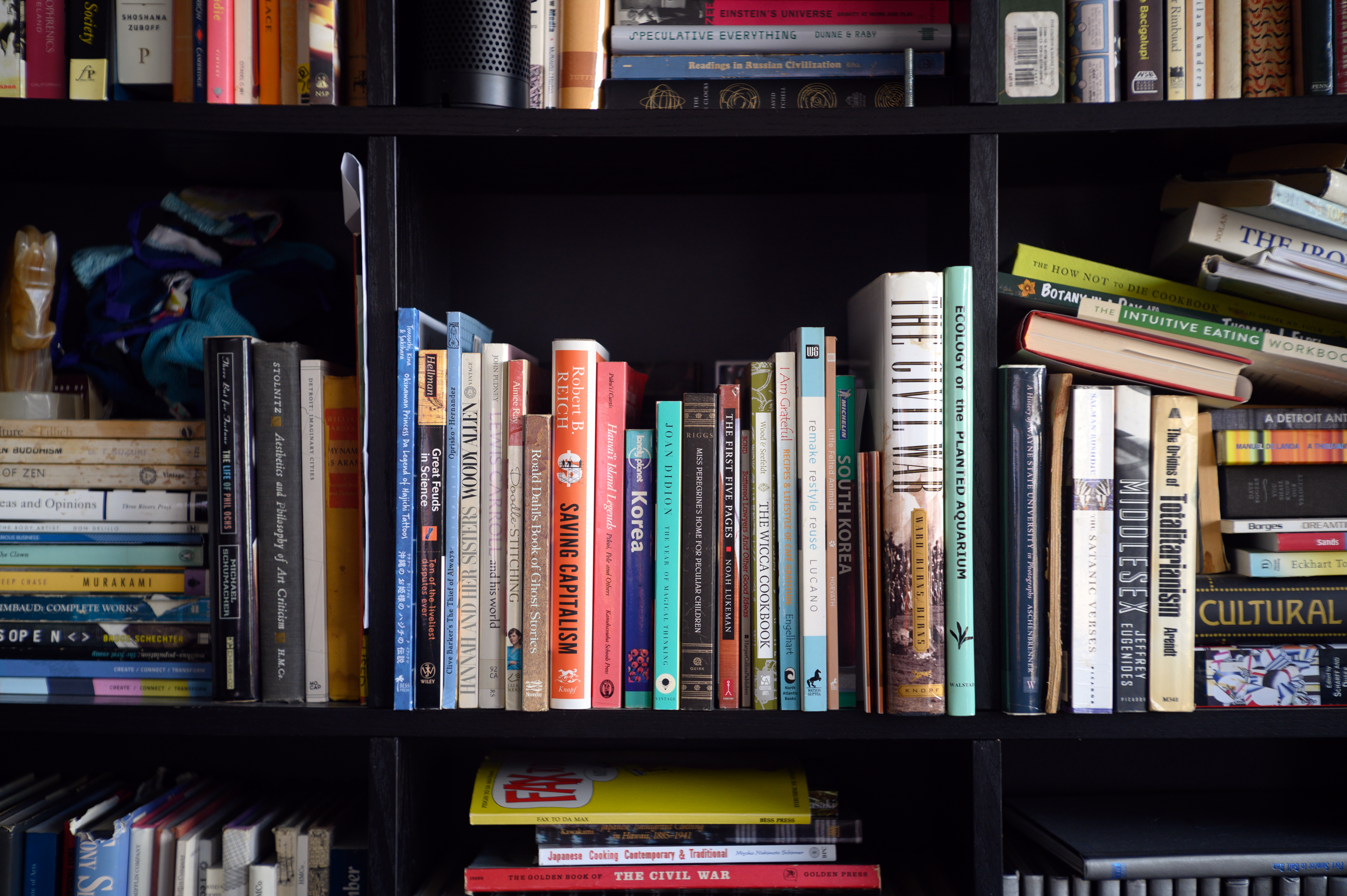

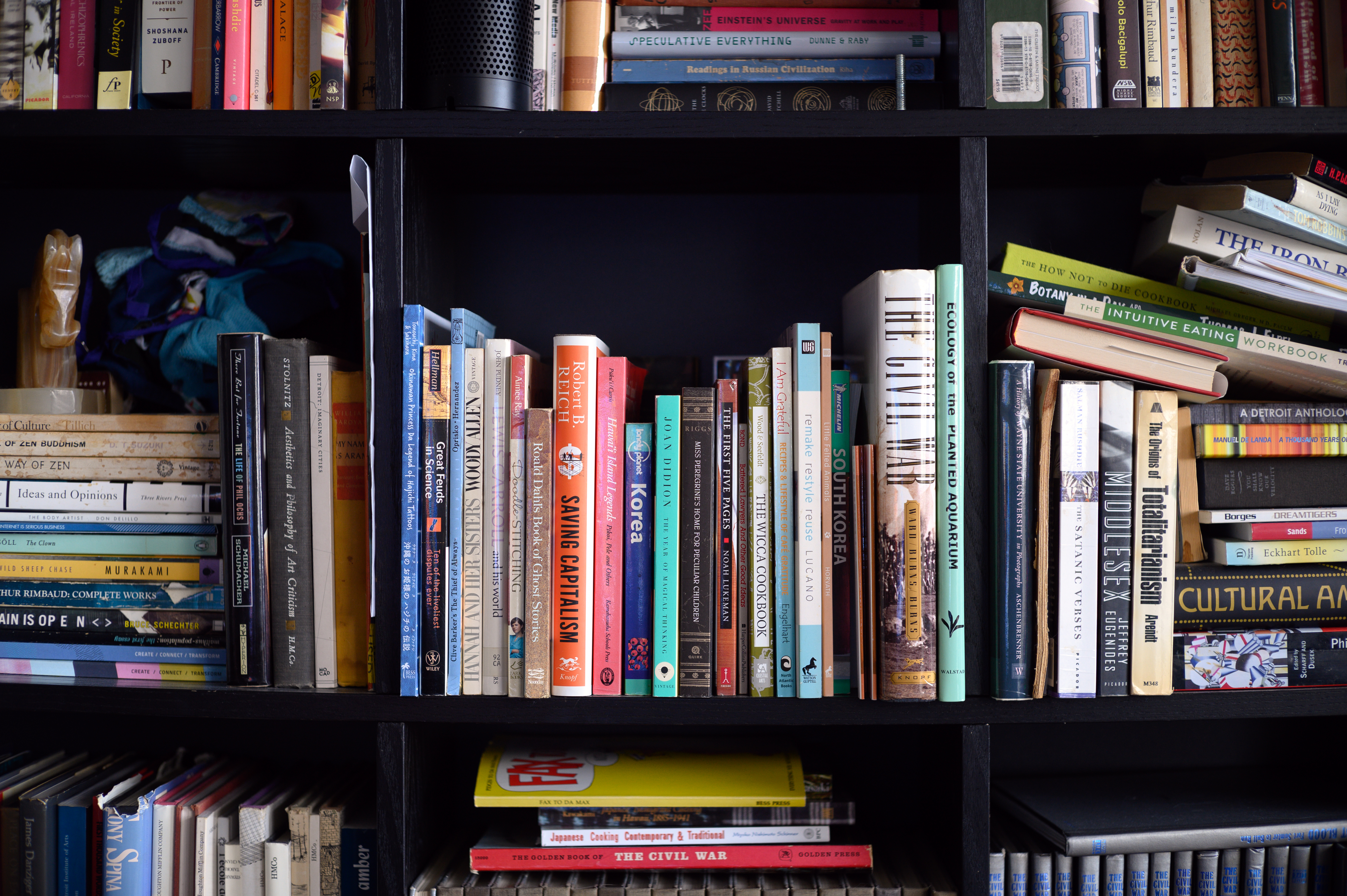

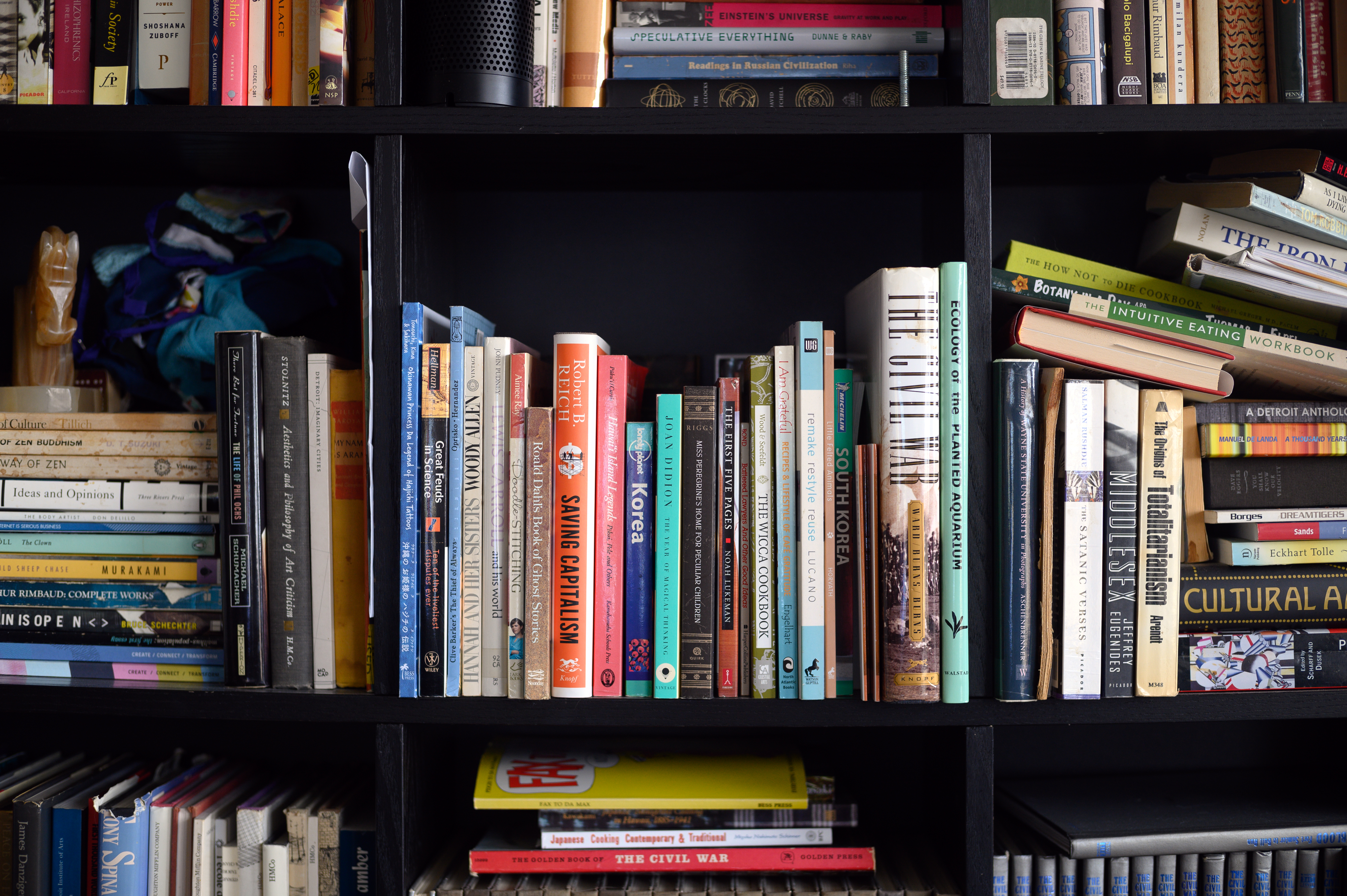

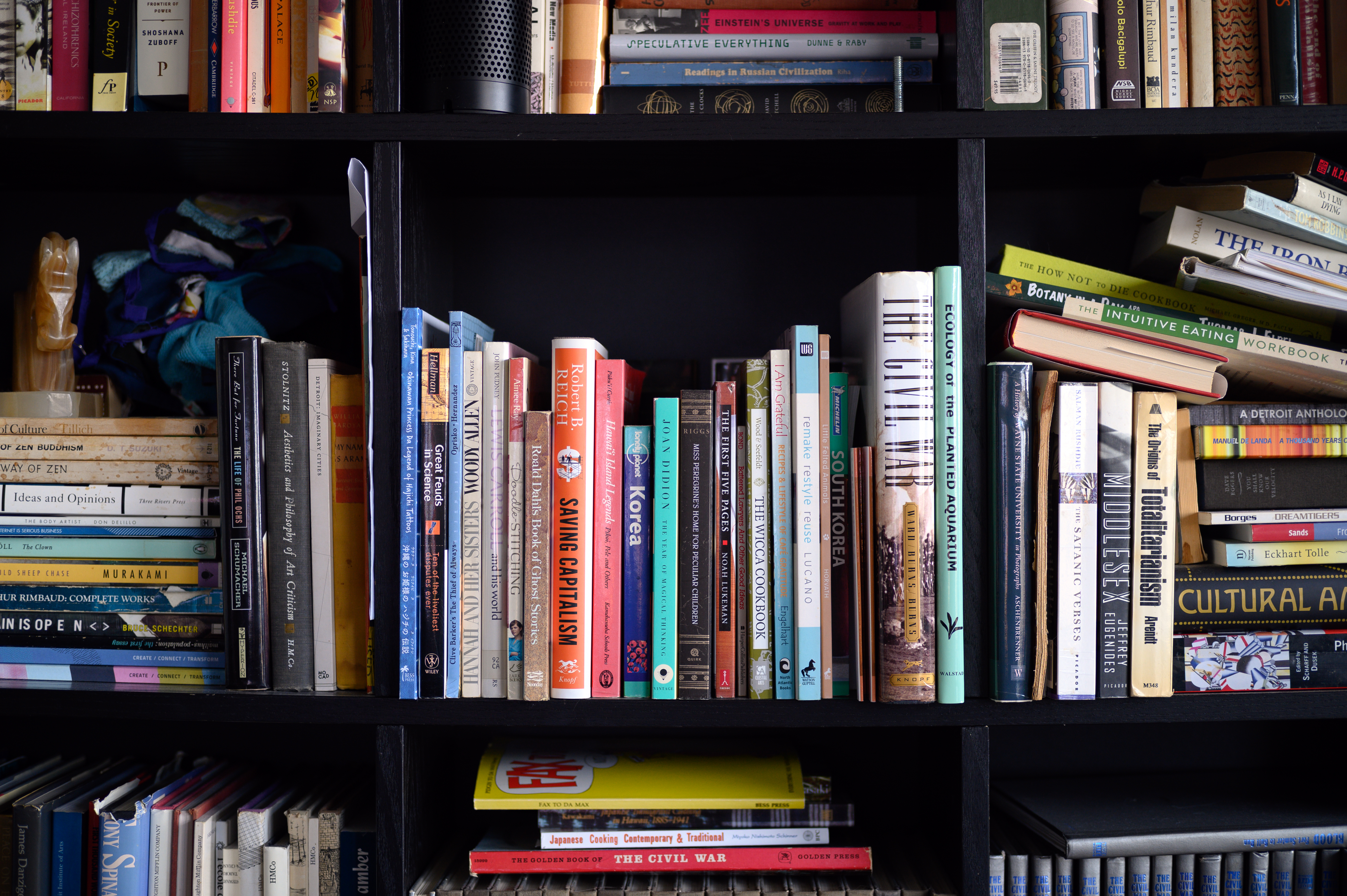

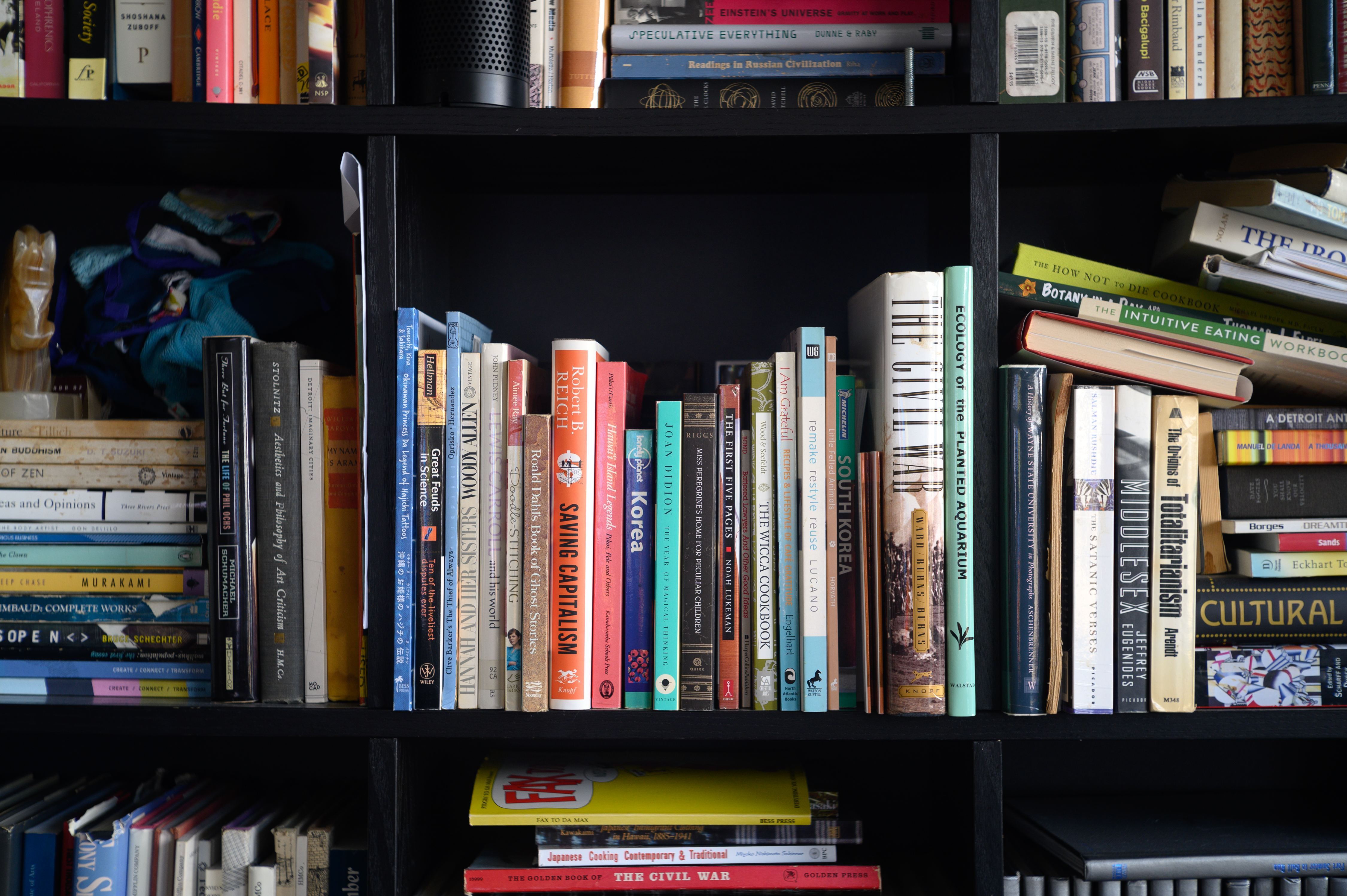

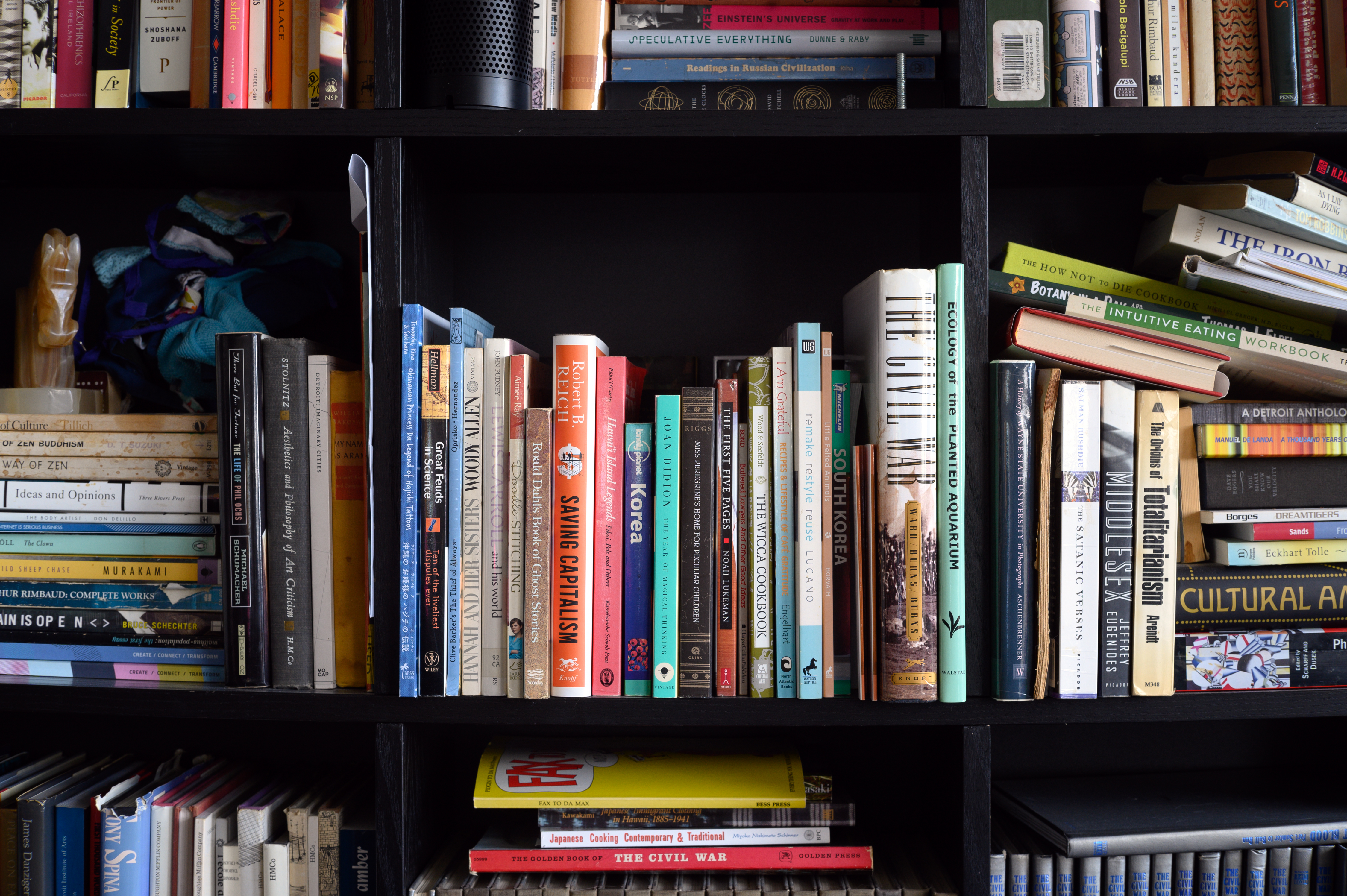

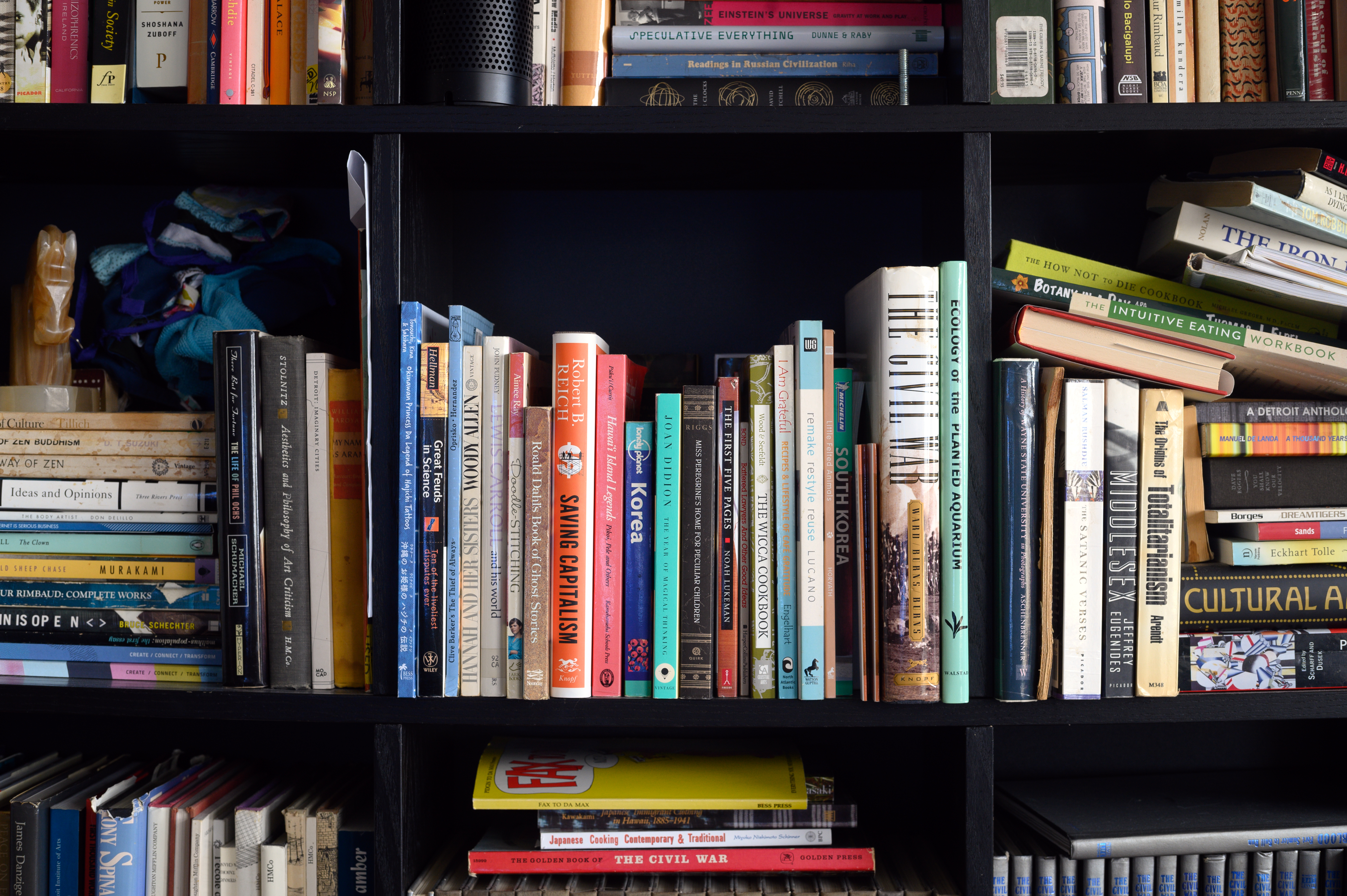

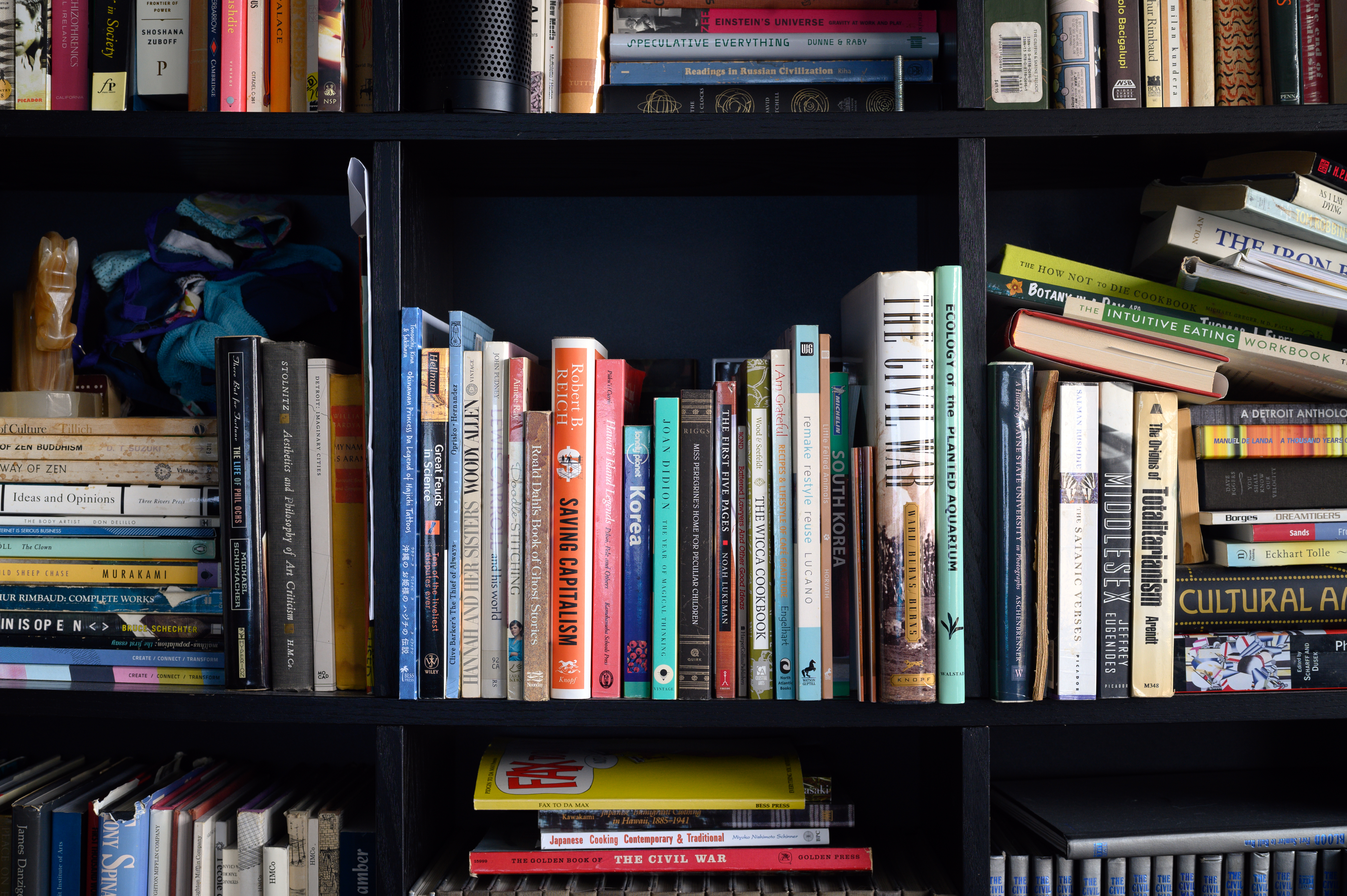

Bookshelf Test

f/1.4-1.5

f/2

f/2.8

f/4

f/5.6

f/8

Infinity Test

f/1.4-1.5

f/2

f/2.8

f/4

f/5.6

f/8

f/11

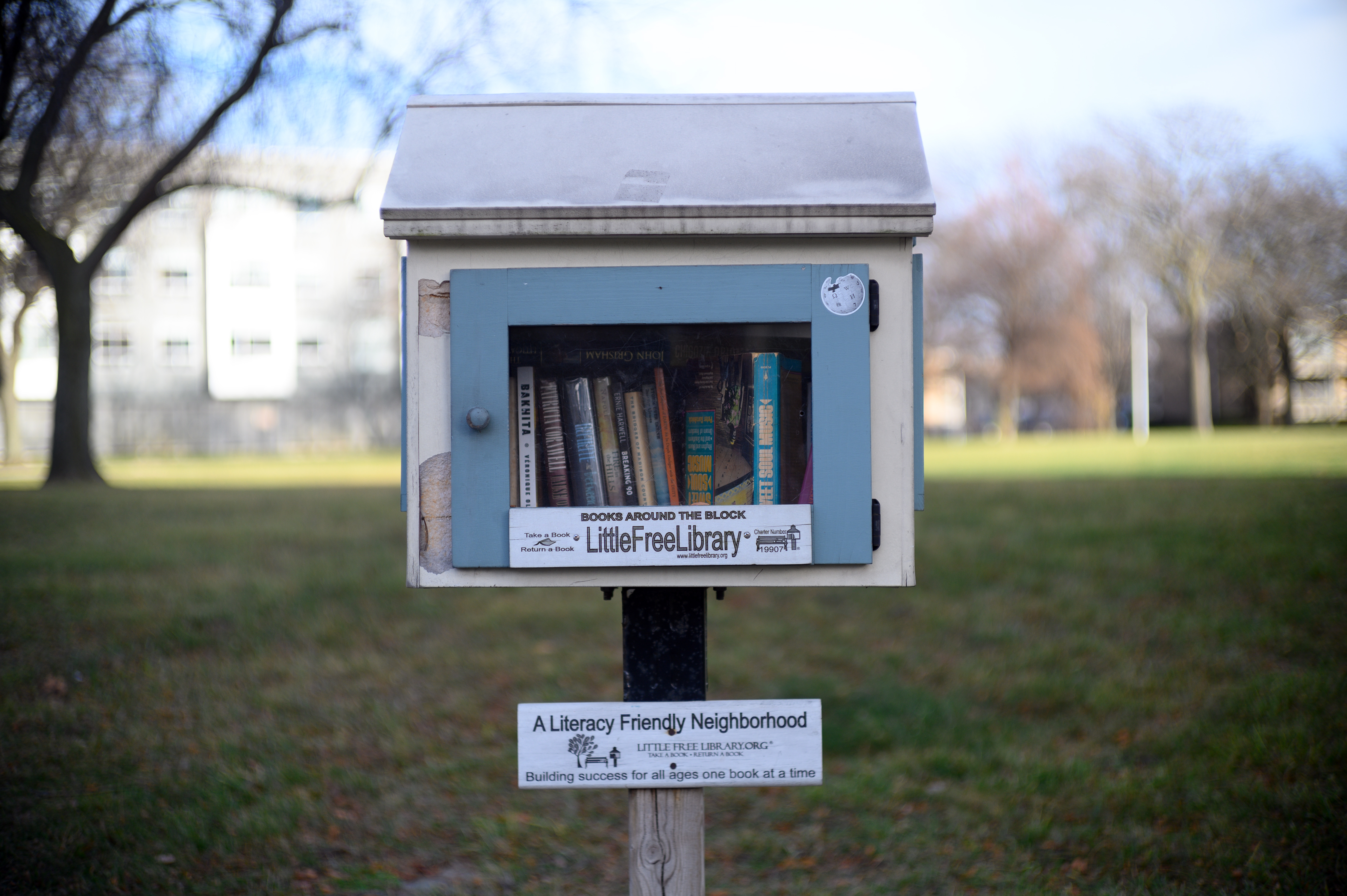

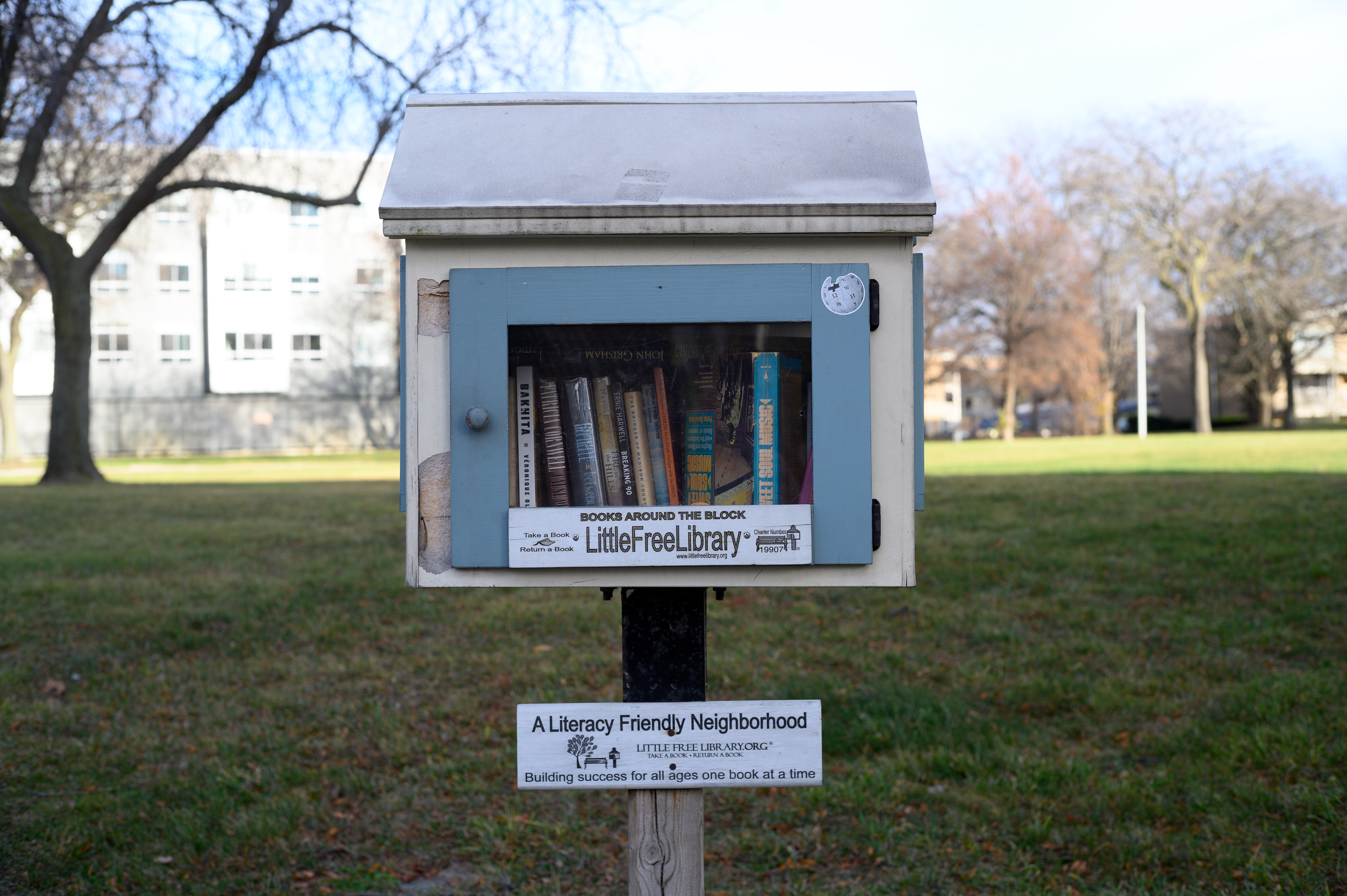

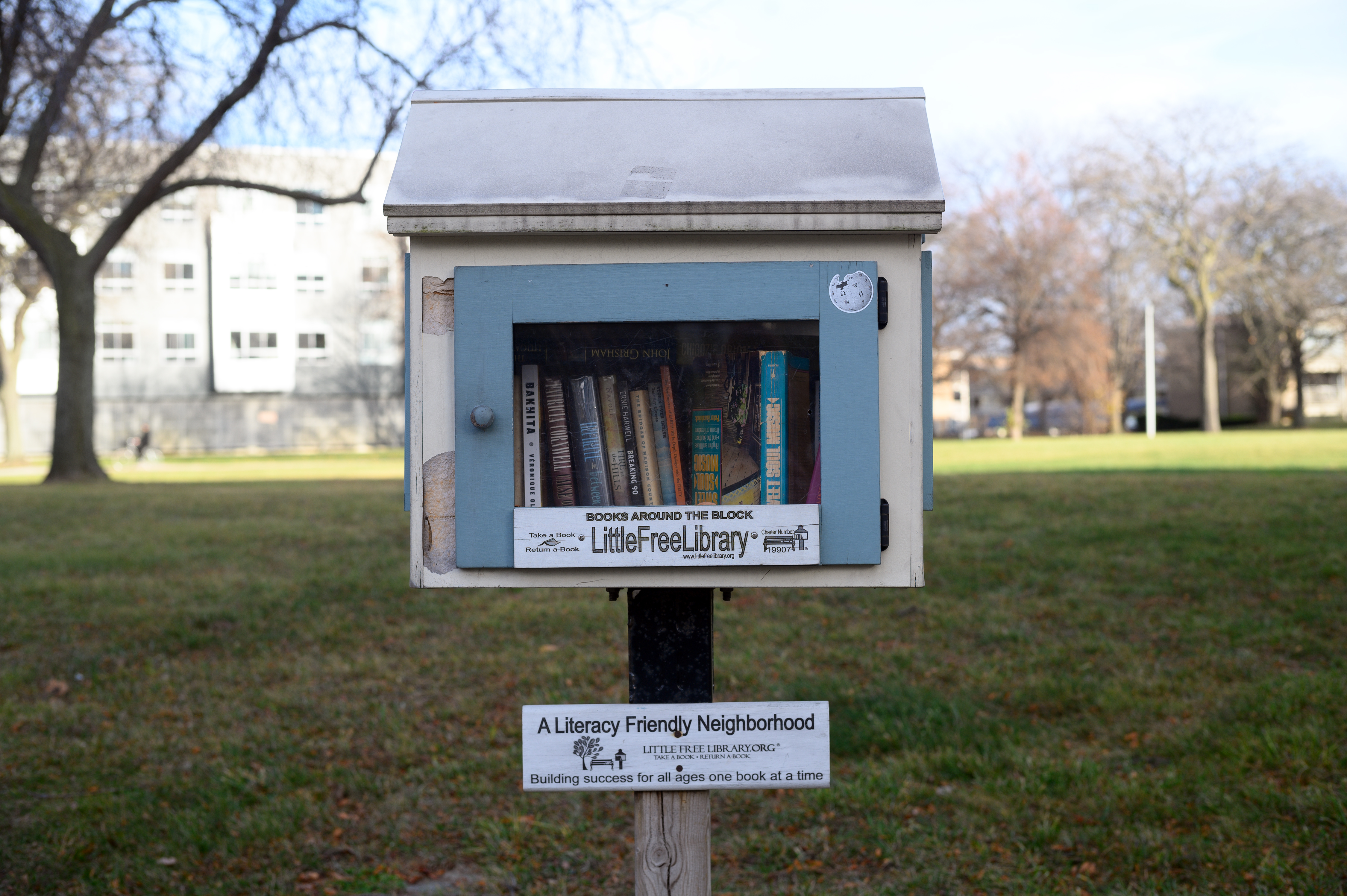

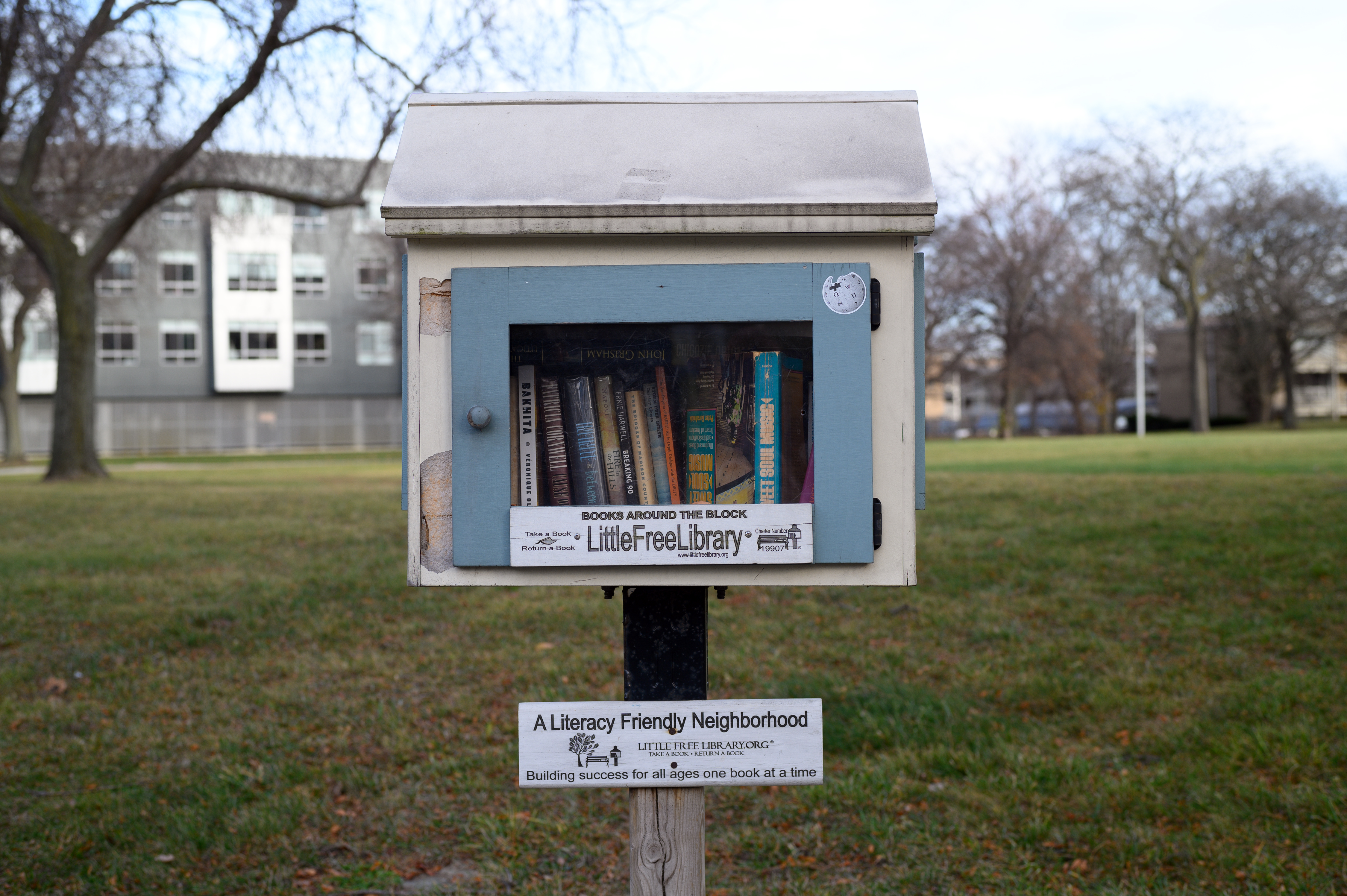

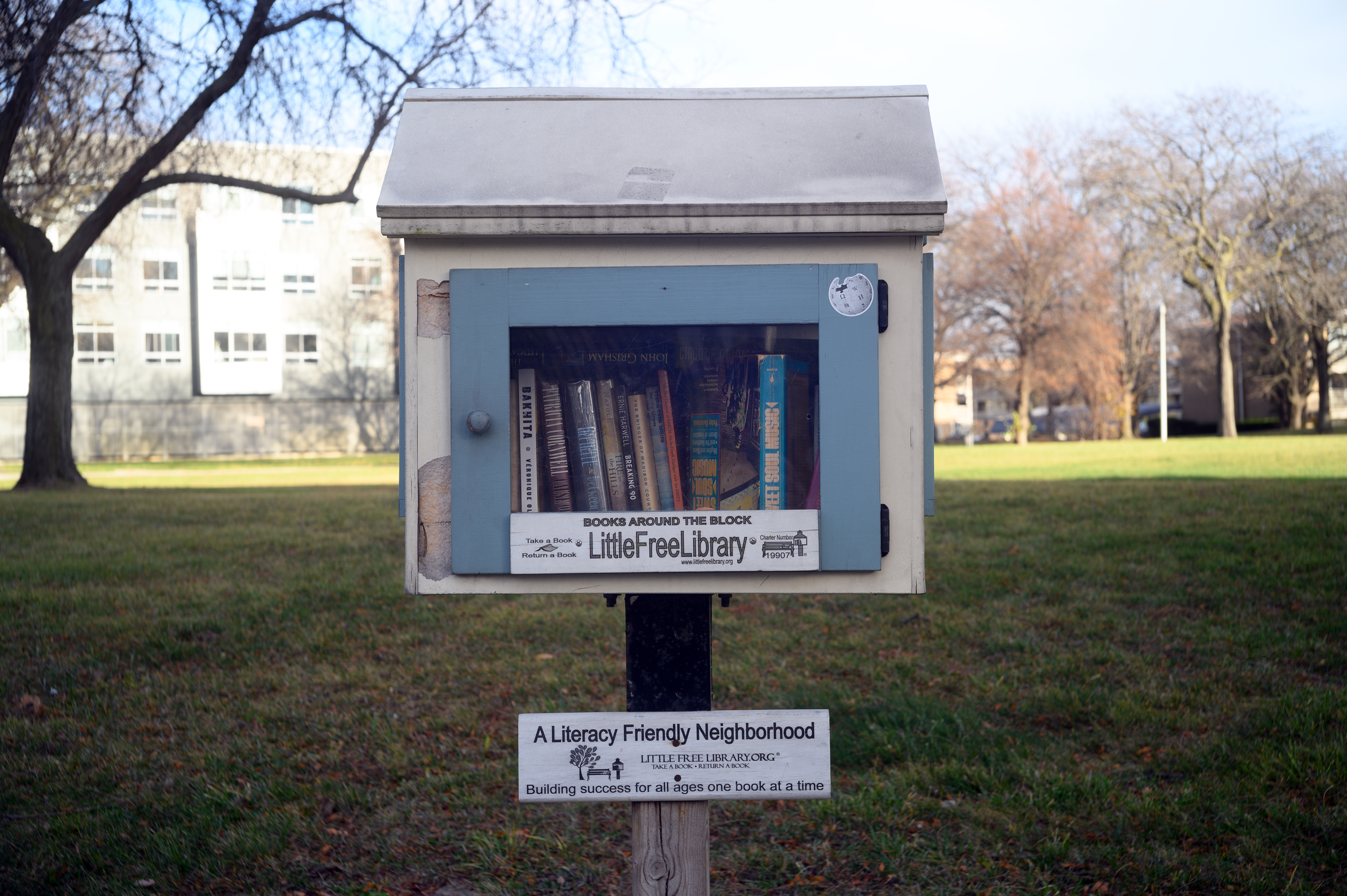

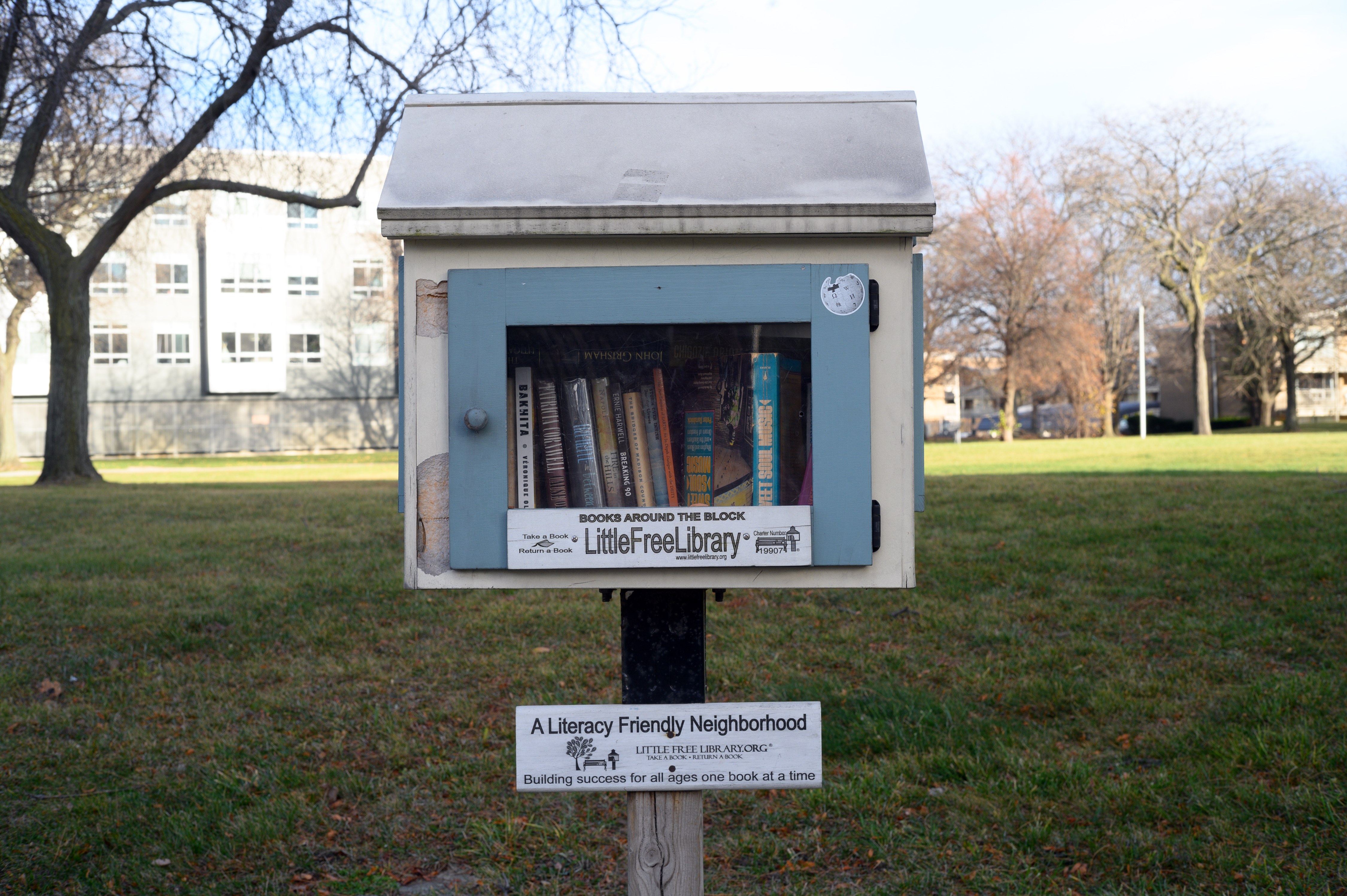

Outdoor Close Up Test

f/1.4-1.5

f/2

f/2.8

f/4

f/5.6

f/8

f/11

Assessment

So what are we seeing here?

Overall, the M-Hexanon is clearly the best “all-around” lens of the four — followed by the Nikkor-S, the Canon, and the Jupiter-3. But there are certainly plenty of nuances.

Despite center sharpness being fairly good for centered close-up subjects, the main problems with the Jupiter-3 are flare, coma, light fall-off, and weak corner performance. The flaring appears at all apertures, at its worst wide-open, but gets progressively better as the lens stops down. The light fall-off continues to about f/4-5.6. At no aperture do the outside parts of the frame resolve as well as any of the Japanese lenses. The ancient single lens coating of the Jupiter-3 is likely responsible for the flaring and coma. The emphasis on centered subjects at closer distances is characteristic of older Sonnars. Weirdly, my Jupiter-3 has trouble focusing to infinity with a standard Leica M to Nikon Z adapter — doubly weird because usually these conservatively-designed adapters permit the “overfocusing” of infinity with most lenses. The Jupiter-3 does render a “warmer” color image than the Japanese lenses. The distortion appears to be of the minor pincushion variety, but it is not that noticeable in everyday situations. To me, out of the box, the Jupiter-3 may be a “two aperture” lens — for close up shots at f/2-2.8, or for distance shots at f/8-11.

The other three lenses can be considered “all-around” 50mms — that is to say that they can shoot well throughout their range. They all have similar low-levels of barrel distortion and good field curvature control. The Canon is a far better lens than the Jupiter-3 by just about every metric. Although the Canon also flares at wider apertures, it is not as bad. The Canon also has better corner performance and better center resolution than the Jupiter-3. Light fall-off in the corners is noticeable until about f/4. The Canon really nails it at f/8. However, it is consistently behind in all major metrics to the M-Hexanon and the Nikkor-S.

The Nikkor-S and the M-Hexanon are perhaps the most similar of the bunch. While the Nikkor-S also has some flare at f/1.4-2, it pretty much is gone after f/2. The M-Hexanon is pretty much flare-free at f/2 and renders a sharper image across the entire frame. However, the Konica does seem to have some purple fringing at f/2-2.8. While the Konica certainly outpaces the Nikkor-S from f/2 to f/4, the lens performance between the two is pretty much indistinguishable at f/5.6 and smaller. At f/5.6-f/11, the performance differences generally among the Canon, the Nikkor-S, and the Konica are small, but noticeable upon a critical look.

Focus Shift

Focus shift is a phenomenon present in varying degrees in most lenses were the point of focus shifts at different apertures. Focus shift is not really an issue for mirrorless cameras because most of the time, the user is focusing a lens at the effective aperture for that shot in real time — in other words, in aperture priority mode, the user sees the actual focus point of the lens at a particular aperture. However, for film and for rangefinder use on a digital M camera, 50mm lenses have a much shallower depth of field and by their nature have less tolerance for focus shifting.

In this group of lenses, the Jupiter-3 demonstrates the most amount of focus shift — in this case, pretty extreme backfocusing at the lens is stopped down. This phenomenon exists throughout its aperture and focus range. The shift is severe enough that under a close look one would probably notice it on film. With a digital M, you should determine at what aperture your Jupiter-3 lens is focusing accurately with the rangefinder — with many Sonnars, this is going to be somewhere around f/1.5-2.8. The other three lenses have some shift, as most all lenses do, but it will be nothing to worry about on mirrorless digital or on film.

Conclusions

In a certain sense, these types of tests are silly because all four lenses are capable of delivering outstanding images — especially on film. However, the above photos reveal maybe what we should have known all along. In overall performance, the M-Hexanon 50/2 is the clear winner. In turn, the Nikkor edges out the Canon. The Jupiter-3 comes convincingly in fourth. However, remember that the M-Hexanon and the Jupiter-3 may need a collimation adjustment to work perfectly with Leica M bodies.

Besides raw optical performance, an important consideration for any of these lenses is the minimum focusing distance. Almost all modern rangefinder lenses can focus at least down to 0.7m (some even closer for digital use). Only the M-Hexanon can focus to 0.7m, while the Nikkor is only 0.9m, and the Canon and Jupiter-3 are only 1.00m. Although 0.3m may not seem like much (about one foot), it makes a big difference in how close you can get to your subject.

Although not a subject of this piece, now over 20 years old, and not an 1.4 lens, the M-Hexanon remains a really good value ($450-600); but we would imagine that many of the Zeiss and Voigtlander modern 50mms probably have surpassed it by now. The Canon ($250-350) is plentiful and cheap. The Nikkor-S is going to be a little difficult to find as a standalone lens and will require a custom adapter ($250 for an adapter any $600-800 for the lens). Jupiter-3s are everywhere, and prices fluctuate; but one can find good examples in the $100-200 range — and unless you can DIY it, most of these lenses will require the additional expense of a collimation check.

At the end of the day, any these older lenses are fun to use, capable of delivering outstanding images, and good values. However, these tests confirm the general rule, and our experiences in testing lenses, that modern lenses are almost always better “all-around” performers than “classic” lenses. Happy shooting!

If you enjoyed this article, please feel free to leave a comment below. We would love to hear your feedback.